Italy: The end of the systematic denial of data protection rights?

Topic

Country/Region

04 March 2025

Italy has been systematically denying people access to data about them stored in Europe’s largest policing and immigration database, statistics obtained by Statewatch show. Much of the data in question concerns entry bans and deportations orders. Knowing what information is stored is vital for peoples’ livelihoods and even their survival. EU institutions have known for years that mechanisms for the protection of individual rights were lacking. Now, victory in a long legal struggle may force the Italian state to comply with its obligations.

Support our work: become a Friend of Statewatch from as little as £1/€1 per month.

Image: Shimona Carvalho, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

“Privacy and data protection are part of the human rights too often suspended at the borders of the European Union. They are rights, which marginalized individuals, stateless families, and migrant communities too often see discarded.”

These were the words of Wojciech Wiewiórowski, the EU’s data protection chief, on International Data Protection Day, 28 January, last year.

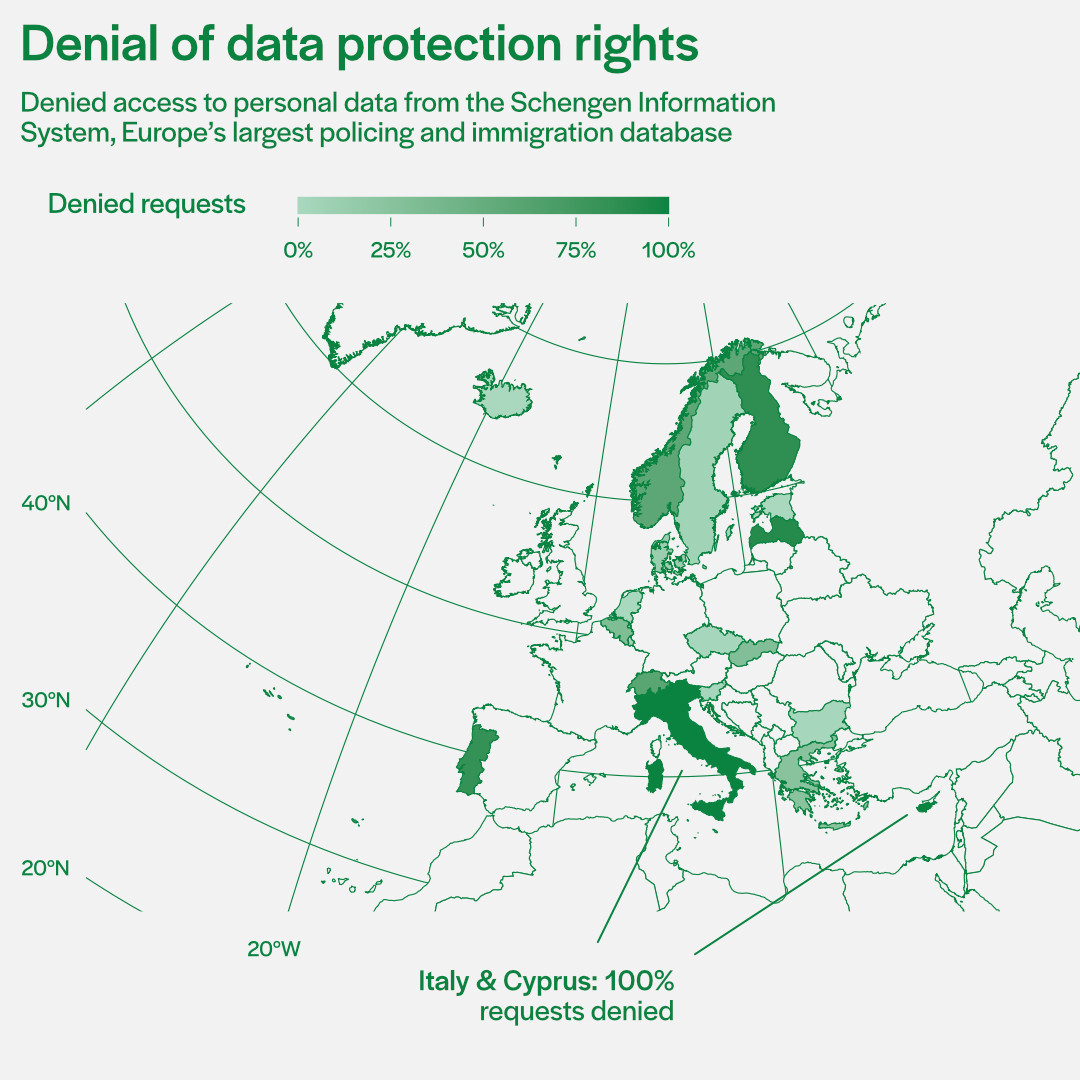

The problem Wiewiórowski was pointing to is visible in data obtained by Statewatch. In 2023, Italy denied all requests from people seeking access to data about them stored in the Schengen Information System, a huge EU policing and immigration database.

This systemic denial prevents people from knowing what data is stored about them, how it is being used, and whether it is accurate or not. It is at odds with Italy’s data protection obligations and the practices of other EU member states. It is clearly absurd.

Following a recent judgment by Italy’s highest court, it may also have to change.

But to understand that judgement, it is necessary to understand the context - and examine the Schengen Information System, the opacity of the Italian state, the inaction of the EU, and people’s right to access their data.

Schengen Information System: use and abuse

The second-generation Schengen Information System (SIS II) is the oldest and largest EU policing and immigration database. It stores information (“alerts”) on people and objects, entered mostly by police, migration and judicial authorities.

The majority of SIS alerts on people are entry bans and deportation orders. In 2023, these two categories made up 66% of the total number of alerts on people in 2023. There are more than 600,000 entry bans stored in the SIS, and more than 321,000 deportation orders. Entry bans are meant to prevent people deemed dangerous or unwanted from traveling to Italy, or any other Schengen state.

However, exactly who is “dangerous” or “unwanted” is open to interpretation. Recently, the French authorities placed an entry ban on the director of a British NGO. The ban was to stop him presenting a report critical of France’s Islamophobic counter-terrorism policies.

Germany placed an entry ban on a Palestinian surgeon, Ghassan Abu Sitta, to stop him from participating in a conference denouncing the genocide in Gaza. There are multiple other explicitly political cases of entry bans known to Statewatch.

The right of access

The European Data Protection Supervisor, the EU data protection authority, describes the right of access to data as “one of the core elements of data protection.” It is “a vehicle for transparency and accountability on how individuals’ data is processed.”

Through the right of access, individuals can request information held about them and rectify or delete any incorrect or unlawful information. The right can also help understand the reasons for a decision (for example, an entry ban) and obtain access to remedies for wrongdoing.

For example, someone who has a request for asylum refused might ask for the relevant national authority for their file. This would allow them to understand the arguments and the facts used in their case to inform an appeal.

The scope of the right of access is a matter of ongoing dispute. A forthcoming case at the Court of Justice of the EU asks whether granting access to an individual’s asylum file should also mean providing “information on the manner in which that information was gathered and obtained.”

A 2014 judgment provided a restrictive answer to a similar question, but was effectively reversed two years later. Legal struggles such as these are likely to become more frequent as the authorities gather more and more personal data, particularly from non-citizens.

Italy singled out

Almost two years ago, new laws came into force expanding the Schengen Information System. The laws increased the types of data collected and the number of authorities with access. However, they also introduced new, albeit limited, transparency requirements.

Under the revamped laws, national data protection authorities must produce annual statistics on the exercise of the right of access (set out here and here).

Those statistics are sent to the European Data Protection Board (EDPB). This body is composed of the head of the data protection authority of each EU member state, as well as the European Data Protection Supervisor. The EDPB’s job is to ensure data protection law is applied in a consistent way across the EU.

Last year, Statewatch made an access to documents request for the first set of national statistics on the right of access sent to the EDPB. The response contains information from the 18 states whose practices are in the latest Schengen Information System legislation.

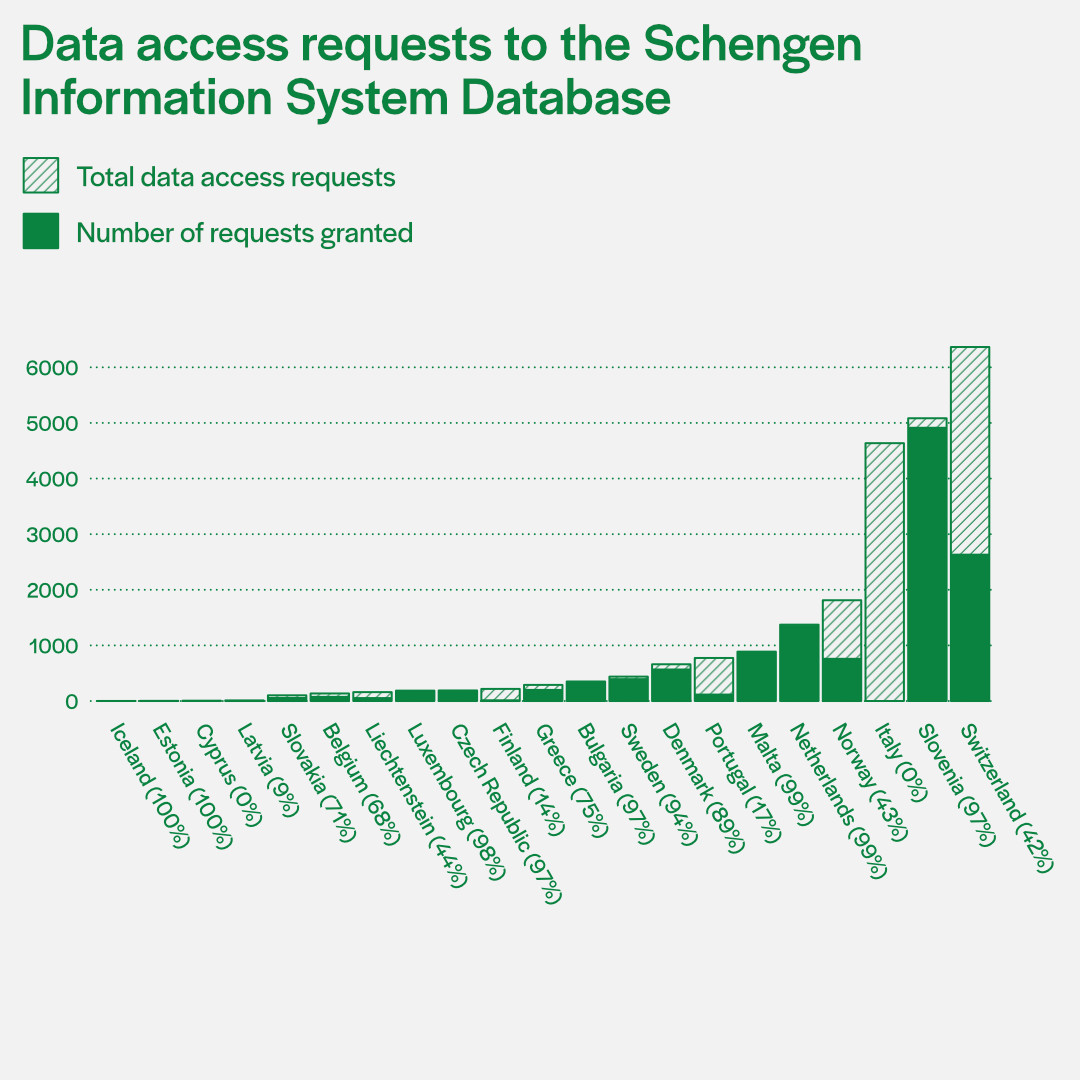

According to the data, individual requests for access to data in the SIS were successful in an average of 65% of all cases. However, the authorities in two states had only one answer to every single access request they received: no.

Those two states were Cyprus and Italy. The Cypriot authorities received just six requests in 2023. Italy, however, denied access to 4,636 requests. In 373 of those cases, an appeal to the national data protection authority was filed, but none were successful.

This map shows the response rate for the countries for which information was provided in response to our request.

More than 4,500 requests for access, all denied. In most cases, the people filing those requests were seeking information about entry bans or deportation orders. These decisions have a profound impact on people’s livelihoods and, in some cases, their survival.

For decades, the EU has kept tabs on how many alerts each country registers in the SIS. Italy has always been at the top of the league, with at least 20% of the alerts in the system. At the end of 2023, 212,543 alerts on persons in the SIS were registered by Italian authorities.

How can a country responsible for storing and sharing so much information on individuals systematically deny them the right to access their data, an essential data protection right?

While the number of people seeking access seems high - 4,636 requests in 2023 - this cannot, in itself, provide an answer. Having to deal with a large number of applications is not a valid reason to deny access. In any case, this amounts to just over 2% of the people whose data is registered in the SIS by the Italian authorities.

Statewatch asked the Italian data protection authority why it systematically denies requests for access to alerts in the Schengen Information System. They did not respond.

Exercising the right of access: an old problem

The Italian practice does not come from nowhere.

In 2014, data protection authorities complained that most countries did not provide reasons for refusing access to data stored in the SIS. They noted that there are “cases when a blanket refusal to access data, drafted in general terms, is necessary, especially in the context of on-going investigations.”

“However, it is recommended to always make a prior assessment on a case by case basis, in order to avoid bulk blanket refusals by default,” their report went on to say.

They called for decisions refusing access to be “duly substantiated and made available for national [data protection authorities], if requested for the performance of their supervisory tasks.”

In a 2023 judgment, the Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU) cleared up the uncertainty. It ruled that blanket refusals to access requests were unjustifiable. National authorities must document why a restriction has been invoked, even in cases involving national security.

The judgment also said that there needs to be a dialogue between law enforcement agencies and data protection authorities to assess the proportionality of restrictions. Furthermore, national courts should be able to assess all the reasons invoked by the authority for processing data and restricting access to it.

The EDPB has made efforts to encourage the exercise of data subject access rights in relation to the SIS. It launched an information campaign in 2021 about the SIS and the right of access. In 2023, it published a guide on exercising the right of access.

However, the guide has shortcomings. It does not explain the types of information that law enforcement authorities should provide to data protection authorities and to individuals to justify a refusal of access. This also ignores the elephant in the room revealed by the 2023 data: in some countries, such as Italy, access to data is a promise never granted.

There are broader concerns about the role of the EDPB. The academics Lisette Mustert and Cristiana Santos argue that because the EDPB’s guidelines lack any binding force, they may create “varying interpretations” of EU data protection law.

The EDPB is obliged to send its report on the right of access to the European Commission, the Council of the EU and the European Parliament. There is no legal obligation to make it public.

Ensuring the right of access: who is responsible?

When Statewatch asked the EDPB about the Italian authorities’ blanket refusal of access requests, the EDPB said that they were “not able address this question.” They recommended directing any questions to the Italian data protection authority.

The European Commission, which is ultimately responsible for ensuring the application of EU law, could also follow up on the issue.

In 2003, the Commission launched legal action against Spain over a similar question.

The Spanish authorities refused visa applications made by non-EU family members of EU citizens. They justified the refusal on the grounds that those family members were listed in the Schengen Information System.

In the case brought by the Commission, the Grand Chamber of the CJEU ruled, in 2006, that Spain should have verified whether the reasons for the alert were genuine, present and sufficiently serious.

In the Spanish case, the matter was not about data protection but about obtaining an effective remedy for a visa refusal. Nevertheless, in both cases, national security grounds are presented as a sufficient justification to refuse a request by a third-country national for further information.

But long gone are the days of the Commission actively pursuing states for breaching the law, through what are known as infringement proceedings. The number of cases filed against EU member states has plummeted.

According to a study the scholars R. Daniel Kelemen and Tommaso Pavone: “Between 2004 and 2018, infringements opened by the Commission dropped by 67%, and infringements referred to the ECJ [Court of Justice of the EU] dropped by 87%.”

This has been particularly concerning for cases touching on the respect of the rule of law, according to a study by the academic Kim Lane Scheppele. There are similar problems in relation to the EU’s immigration laws, according to Maciej Grześkowiak.

A document obtained by Statewatch offers a glimpse into how deficiencies in respecting the law are being addressed by EU institutions.

A 2021 evaluation of the Schengen acquis (the set of rules that regulate the abolition of border control between EU member states) identified several deficiencies in Italy. In particular, the report recommends the Italian authorities change the standard response provided to individuals seeking access to data stored about them in the SIS.

The standard response from the Italian authorities was that ”the data subject has no entry bans in the Schengen Territory.” The evaluation described this as “misleading” in cases were the information was held, but was denied “for instance due to threats to public or national security.”

So, not only were people facing entry bans or deportation orders denied access to their data without justification, but they were also told that there was no information stored about them.

Three years after this report landed on the desk of the European Commission, the practice remained the same. Thousands of people have been lied to and denied access to redress.

This chart shows the response rate for the countries for which information was provided in response to our request.

Justice at last in Italy

One of the exceptions to the right to access one’s file concerns questions of “national security.”

This exception recently faced scrutiny in the highest Italian appeal court. In a case that lasted more than 15 years and ended up at Italy’s Court of Cassation, Muhamed Dihani won.

Dihani was arrested by the Moroccan authorities in 2009. He was charged with incitement to terrorism because he campaigned for the independence of Western Sahara, a territory under unlawful Moroccan occupation. Western Sahara is an independent territory whose population has a right to self-determination recognised by the United Nations.

He was detained for four years in Morocco, where he was tortured. After he was released, he left the country and tried to reach Italy, to seek treatment and rehabilitation.

Where Dihani went, the Moroccan authorities sent information to follow him. He applied for a visa to enter Italy but was refused because of an alert in the Schengen Information System: he was deemed a threat to national security because of his involvement in terrorism.

For years, the Italian authorities refused to give access to the file, which would have made it possible for him to contest the accusation. Judges involved in the case were also denied access to the information.

At the end of January, the Italian Court of Cassation ruled that the entry ban should be discarded due to its basis in the information sent by the Moroccan authorities.

In a judgment from last year in Dihani’s case, the Court of Appeal last year had already ruled that judicial authorities should have the “power to supervise and verify the processing of data, even in contexts related to national security.”

Ilaria Masinara, head of Amnesty International Italy's campaigns office, said:

“After this judgement, which could also have an important value for other people belonging to third countries and living in the Italian territory, Dihani will finally be able to access and ask for the deletion of information and data that, until now, have cast a long shadow on his present and future.”

Long overdue changes

When states that signed the Schengen agreement abolished mutual border controls, they also agreed to the cross-border exchange of data. Alongside that, they agreed to guarantee the security of the data and individuals’ data protection rights. Every country signing the convention had to set up a data protection framework and an independent supervisory authority.

The rights of access, rectification and deletion were laid out in the convention implementing the Schengen agreement (articles 109, 110 and 111, respectively). But law enforcement authorities were left to their own devices in implementing the rules.

The founder and former Director of Statewatch, Tony Bunyan, wrote in 2009 that “no survey or review has ever been carried out by the Commission or any other body as to the rights and protections or limitations [regarding the SIS] that exist from state to state under national laws.”

The first statistics ever produced on the effectiveness of the right of access in the Schengen Information System – the statistics that show Italy’s blanket denial of access – are damning. The country creating more alerts on individuals than any other has completely ignored data protection rights.

EU law-makers have revised the legislation governing the SIS three times since the system was first set up. But more transparency and redress have only come through the painstaking work of individuals fighting for their rights in court.

Dihani’s judgement is a testimony to the fact that individual victories remain vital, particularly when they have broader effects, such as widening people’s right to access their files.

The judgment is long overdue but is also timely. It comes at a time when national and EU authorities are collecting increasing amounts of data about non-citizens, increasing data-sharing with non-EU authorities, and when data protection authorities have received new responsibilities to oversee the use of artificial intelligence technology by policing and immigration authorities.

Data protection law can help individuals understand the often-faceless bureaucracy of the state, comprehend its inner workings, and the reasons behind decisions that affect them. This is a growing concern in an environment of increasingly automated suspicion.

Author: Romain Lanneau

Graphics: Ida Flik

The data in the tables below concerns data subject access requests made under three pieces of legislation that govern the Schengen Information System:

- Regulation 2018/1860 on the use of the Schengen Information System for the return of illegally staying third-country nationals

- Contains alerts on individuals subject to a deportation order ("alerts on return")

- Regulation (EU) 2018/1861 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 28 November 2018 on the establishment, operation and use of the Schengen Information System (SIS) in the field of border checks

- Contains alerts on individuals banned from entering the Schengen area ("alerts on refusal of entry or stay") - the data discussed in this article

- Regulation (EU) 2018/1862 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 28 November 2018 on the establishment, operation and use of the Schengen Information System (SIS) in the field of police cooperation and judicial cooperation in criminal matters

- Contains alerts on:

- persons wanted for arrest for surrender or extradition purposes;

- missing persons or vulnerable persons who need to be prevented from travelling;

- persons sought to assist with a judicial procedure;

- persons and objects for discreet checks, inquiry checks or specific checks;

- objects for seizure or use as evidence in criminal proceedings; and

- unknown wanted persons for the purposes of identification under national law.

- Contains alerts on:

Note: Data for Switzerland was provided with a total number of access requests across all three Regulations (6,365). This led to the country providing access for all the 2,606 requests for which there was an alert under Regulation 2018/1861 (2,606 requests), and to 14 of the 44 requests for which there was an alert under Regulation 2018(1862). There were no alerts in relation to 3,715 of the total of 6,365 requests.

Regulation 2018/1860

| Country | Number of access requests | Access granted | Access granted (%) |

| Belgium | |||

| Bulgaria | |||

| Czech Republic | 5 | 5 | 100% |

| Denmark | 2 | 2 | 100% |

| Estonia | 0 | ||

| Finland | |||

| Greece | 17 | 14 | 82% |

| Italy | 273 | 0% | |

| Latvia | |||

| Liechtenstein | 0 | 0 | |

| Luxembourg | 8 | 8 | 100% |

| Malta | 61 | 61 | 100% |

| Netherlands | 129 | 129 | 100% |

| Norway | |||

| Portugal | 234 | 129 | 55% |

| Slovakia | 4 | 4 | 100% |

| Slovenia | 704 | 704 | 100% |

| Sweden | 22 | 22 | 100% |

Regulation 2018/1861

| Country | Number of access requests | Access granted | Access granted (%) |

| Belgium | 134 | 93 | 69% |

| Bulgaria | 335 | 335 | 100% |

| Czech Republic | 167 | 167 | 100% |

| Denmark | 659 | 583 | 88% |

| Estonia | |||

| Finland | 109 | 3 | 3% |

| Greece | 259 | 190 | 73% |

| Italy | 4250 | 0 | 0% |

| Latvia | 10 | 0 | 0% |

| Liechtenstein | 1 | 1 | 100% |

| Luxembourg | 164 | 164 | 100% |

| Malta | 805 | 805 | 100% |

| Netherlands | 1178 | 1178 | 100% |

| Norway | 59 | 56 | 95% |

| Portugal | 532 | 304 | 57% |

| Slovakia | 90 | 62 | 69% |

| Slovenia | 4227 | 4227 | 100% |

| Sweden | 389 | 385 | 99% |

Regulation 2018/1862

| Country | Number of access requests | Access granted | Access granted (%) |

| Belgium | 2 | 0 | 0% |

| Bulgaria | 16 | 7 | 44% |

| Czech Republic | 18 | 13 | 72% |

| Denmark | |||

| Estonia | 3 | 3 | 100% |

| Finland | 109 | 28 | 26% |

| Greece | 14 | 14 | 100% |

| Italy | 113 | 0 | 0% |

| Latvia | 1 | 0% | |

| Liechtenstein | |||

| Luxembourg | 15 | 11 | 73% |

| Malta | 22 | 16 | 73% |

| Netherlands | 66 | 59 | 89% |

| Norway | 1739 | 721 | 41% |

| Portugal | 8 | 5 | 63% |

| Slovakia | 9 | 7 | 78% |

| Slovenia | 153 | 0 | 0% |

| Sweden | 28 | 4 | 14% |

Documents received in response to an access to documents request filed by Statewatch with the European Data Protection Board (pdfs):

- Austria

- Belgium (1, 2, 3)

- Bulgaria

- Croatia

- Cyprus

- Czech Republic

- Denmark

- Estonia (1, 2)

- Finland

- Greece

- Hungary

- Italy

- Latvia (1, 2, 3)

- Liechtenstein

- Luxembourg

- Malta

- Netherlands

- Norway

- Portugal

- Romania

- Slovakia

- Slovenia (1, 2, 3)

- Sweden (1, 2)

- Switzerland

Our work is only possible with your support.

Become a Friend of Statewatch from as little as £1/€1 per month.

Further reading

Italian police are “misleading” people about Schengen entry bans, says internal EU report

The Italian police are providing “misleading” information to people who ask whether there is a Schengen entry ban against them, says an internal EU report obtained by Statewatch. The document also says the country’s data protection authority cannot properly supervise the use of two huge EU databases.

Polish government proposes life-long EU entry bans for deportees

In the coming months, EU institutions will start negotiating a new law to increase deportations. EU governments want their positions taken into account in the European Commission’s forthcoming proposal. The Polish government has proposed banning deportees from EU territory for “an indefinite period of time,” alongside other coercive measures.

Spotted an error? If you've spotted a problem with this page, just click once to let us know.