€1,500 and a one-way ticket: how Cyprus deports Syrian refugees with EU support

Topic

Country/Region

17 February 2025

Cyprus has been unlawfully detaining Syrian refugees for years, and has coerced thousands of people to go back to Syria through a supposedly "voluntary" return programme. Behind those "voluntary" returns lies a lack of access to asylum procedures, intimidation by officials, and appalling detention conditions. The European Commission and Frontex have supported the programme, despite internal concerns. EU funds for the Cypriot deportation regime run into the tens of millions of euros, but the real price is paid by Syrian refugees.

Support our work: become a Friend of Statewatch from as little as £1/€1 per month.

This article is co-published with The New Arab and UntoldMag.

Authors: Anas Ambri and Hope Barker

For Abu Iskander Alshami the question of returning to a post-Assad Syria is fraught with uncertainty. “My situation is similar to 90% of Syrians - undecided”, he told The New Arab.

We spoke with Alshami on 17 December 2024, just days after Syria’s longtime dictator Bashar al-Assad fled the country. Originally from Damascus, Alshami has been living in Cyprus for the past nine years.

“Some people cannot go back simply because they do not have a home to go back to. That’s the case for me as well. My home was bombed. I cannot return if it means ending up on the street”, said Alshami.

Over the past year, The New Arab (TNA) has looked into Cyprus’ Voluntary Return Program, the country’s flagship project meant to support individuals who want to return to their home country “in an organised, safe and dignified manner”.

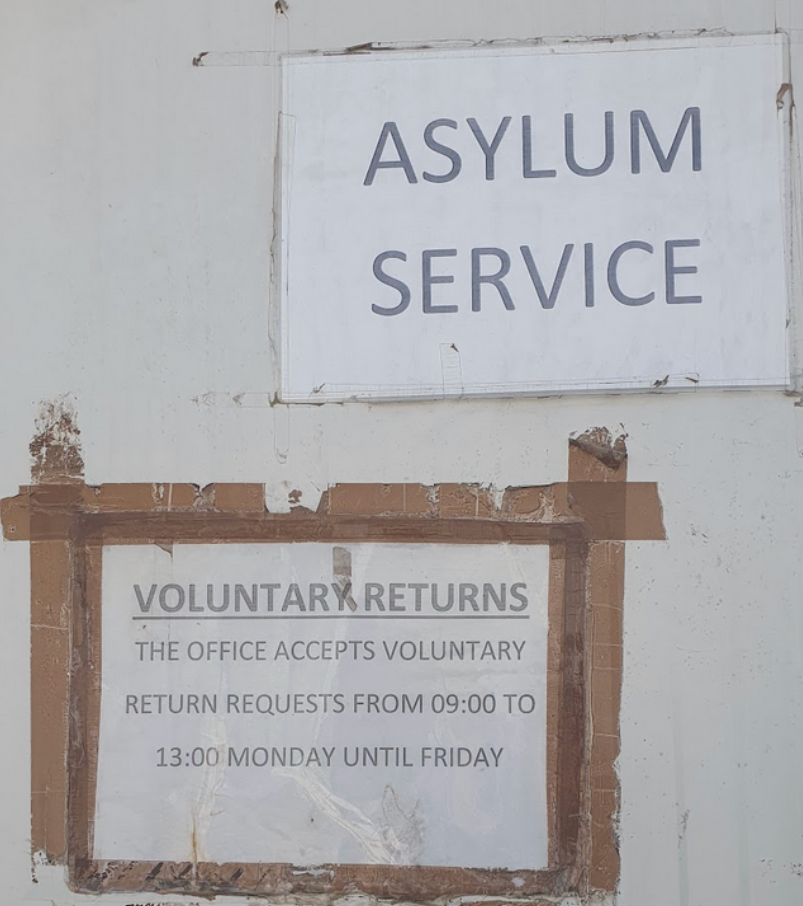

A sign inside Pournara, Cyprus’ main refugee reception centre, advertising voluntary returns to its residents, who are overwhelmingly Syrians. March 2024. (Image: The New Arab)

Our investigation reveals a different reality. The Cypriot ministry of interior is using coercion and deceit to pressure individuals into voluntary returns, at the expense of the country’s obligations under the European Convention of Human Rights.

In the case of Syrian asylum seekers, this includes denial of access to asylum, unlawful detention in conditions “contrary to European values and international human rights law”, and unfounded accusations of serious crime.

Cyprus’ voluntary returns programme is financially and operationally supported by the European Commission (EC) and Frontex, the EU border agency.

The EC has also encouraged more countries to embrace the Cypriot ‘model’ of deportations, spelling more heartache for the more than one million Syrian asylum seekers and refugees living in Europe.

The UN Refugee agency (UNHCR) does not currently promote large-scale voluntary returns to Syria.

TNA contacted the Cypriot authorities, the European Commission and Frontex for their comment on this story. A spokesperson for the ministry of interior referred us to the deputy ministry of migration. Our emails and call to the latter went unanswered.

A spokesperson for Frontex told TNA that the agency does not currently support returns to Syria from Cyprus, or from any other EU state. They added that Frontex' return specialists in Cyprus provide information about voluntary returns only to Syrians who inquire about them "on their own initiative".

No other reply was received in time for publication.

A policy of exclusion

Syrian refugees started arriving in Cyprus in low numbers in 2002. However, the hardening of borders throughout continental Europe in the aftermath of the so-called 2015 refugee crisis forced millions of them to look for alternative ways to reach European shores.

Between 2018 and 2022, Cyprus received the largest number of applications of asylum per capita among all 27 EU states, predominantly from Syrians. Meanwhile, relocations of refugees from Cyprus to other EU countries, meant to more fairly distribute the burden of migration across the Union, remained well below expectations.

Over the past year, EU countries have been pushing for the normalisation of relations with Assad as a first step towards encouraging Syrian refugees to return.

The fall of the Baathist regime has hastened this EU-wide push. Shortly after Assad’s fall, 17 European governments rushed to suspend asylum procedures for Syrian nationals.

In Cyprus, the push for returns is nothing new. Already in April 2024, Cypriot authorities announced that they would stop processing asylum applications from Syrians, including for some who had been in the country for four years.

Newly arrived Syrians are banned from working in their first nine months on the island and often denied access to all forms of material assistance, which has pushed many towards homelessness.

As soon as they arrive in Cyprus, Syrian asylum seekers need to go to Pournara, the country’s main refugee reception center, to initiate asylum procedures. March 2024. (Image: The New Arab)

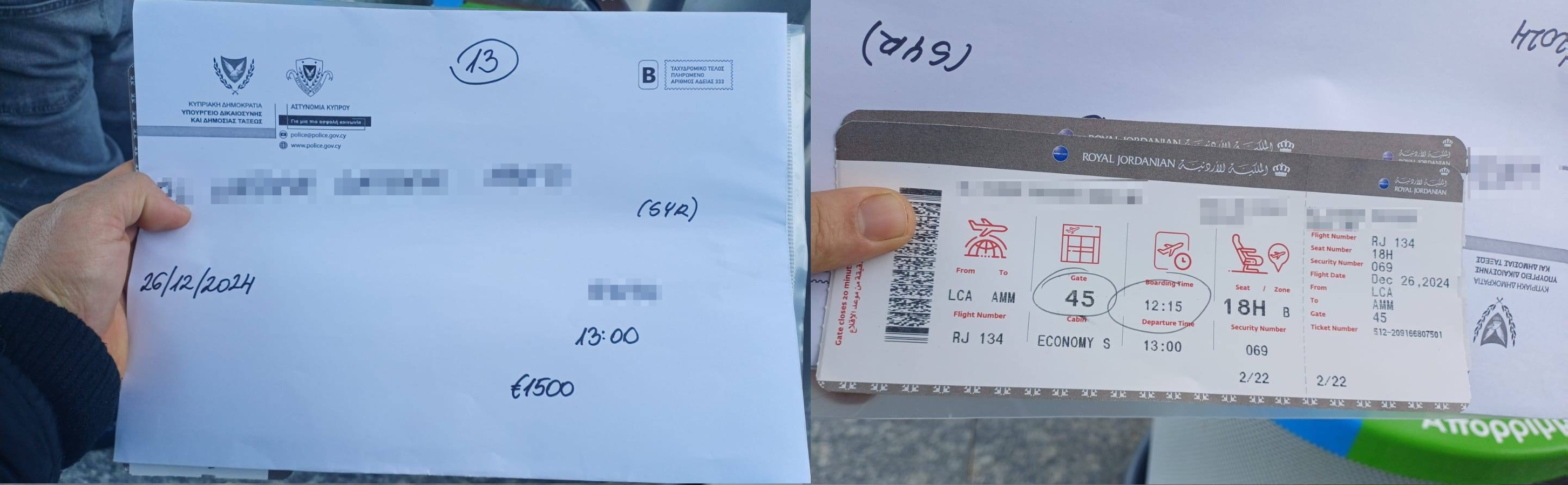

Meanwhile, Cypriot authorities have actively encouraged Syrian refugees to voluntarily return to Syria, offering €1,500 and a one-way ticket to anyone who does so.

Since the fall of Assad, only 755 out of the 30,000 Syrians currently in Cyprus have “voluntarily” returned to their home country, according to government figures. At least 14,000 of them are still waiting for their asylum applications to be processed.

Cyprus: number one in the EU in deportations

On 1 December 2022, speaking at a meeting of the European Commission (EC), Nicos Nouris, Cyprus’ then-minister of interior, proclaimed that his country had achieved first place among EU member states - per capita - in the number of individuals it deported.

According to Nouris, a driving force behind this success was his ministry’s “emphasis on the voluntary return program” which he claimed accounted for 87% of the “almost 7,000” people deported up to that point in 2022.

In reality, only 4,205 people were returned from Cyprus that year, according to the statistical office of the European Union.

Unlike forced returns, "voluntary" returns are repatriations of non-EU citizens to their country of origin “based on a free and informed choice”. However, the overwhelming majority of people who agree to return voluntarily from Cyprus are individuals who have exhausted all legal avenues to stay in the country, and have been ordered to leave.

At around the same time as Nouris’ speech, reports of coercion within Cyprus’ voluntary returns programme started to challenge the narrative presented by the authorities.

On 28 December 2022, online news platform InfoMigrants published the account of Chazel, a Congolese asylum seeker in Cyprus, and his coerced deportation reportedly disguised as voluntary.

Accused of participating in a fight at Pournara, Cyprus’ main refugee reception centre, Chazel was arrested alongside 69 other asylum seekers.

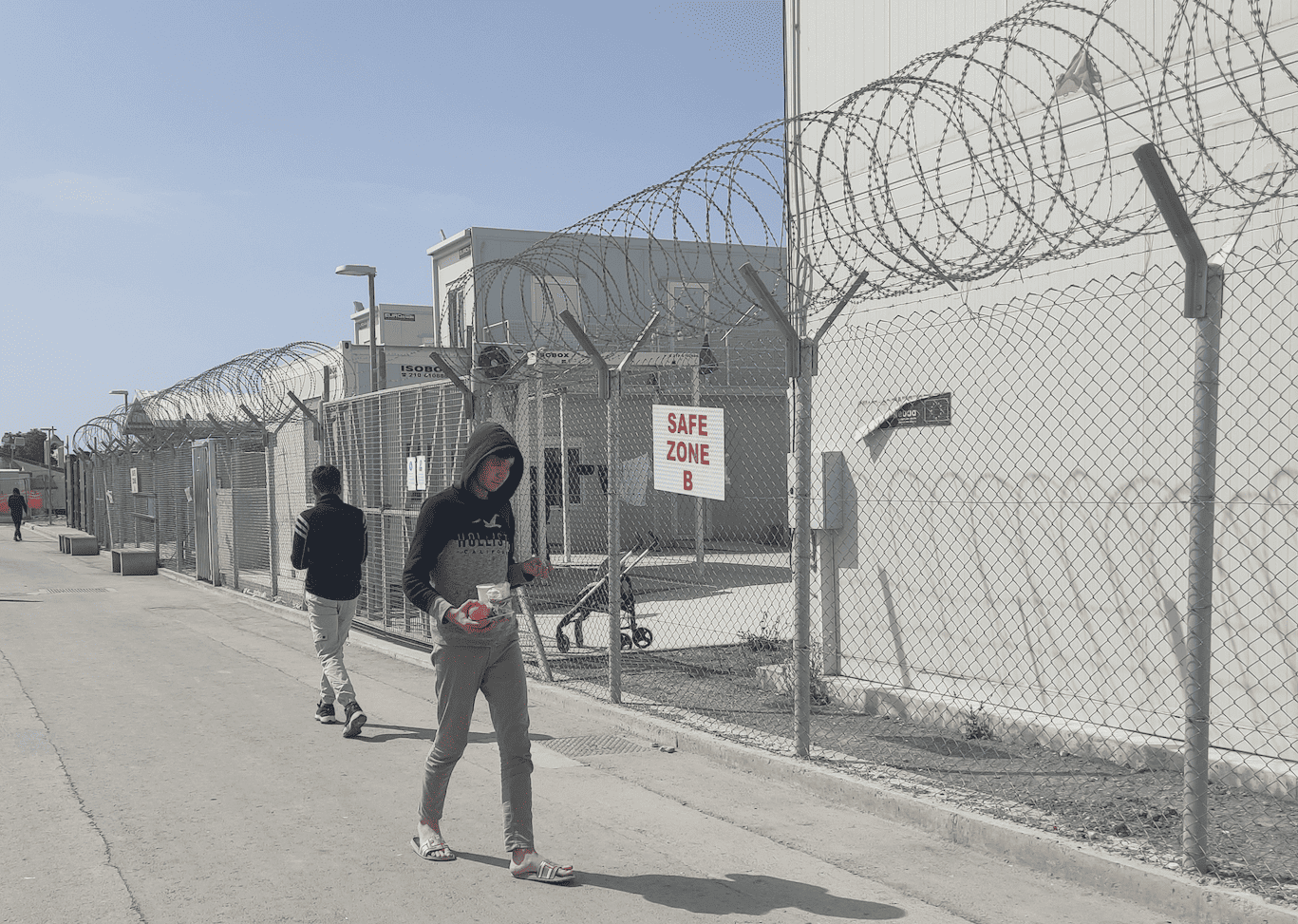

Image taken inside Pournara, Cyprus’ main refugee reception centre, during a visit in March 2024. The Council of Europe’s Committee for the Prevention of Torture consider Pournara to have “prison-like” conditions. (Image: The New Arab)

Instead of a lawyer, the detainees were visited daily by a police officer from the Aliens and Immigration Unit. The officers pressured them to sign voluntary return agreements, under the threat of forced deportation.

While Chazel eventually agreed to his deportation, others were able to challenge their arrest. In at least two cases, judges found that the detention had been illegal. Police had in effect not conducted any investigation into their accusations some nine months after the incident.

The ‘Syrian problem’ inside Cyprus’ detention facilities

Asylum seekers are routinely detained at Menoyia, the island’s sole migrant detention centre, which is used for holding up to 128 people slated for deportation.

When Menoyia reaches full capacity, additional holding cells in 22 police stations across the country are also used, bringing the total capacity to 322 people.

In March 2024, one of the authors of this investigation visited the Lakatamia Police station, as an independent researcher in a delegation of Members of the European Parliament (MEPs). Some of the detainees from the Pournara incident were held in this station.

The Lakatamia Police station, at the edge of Nicosia, Cyprus’ capital city, which the MEPs’ delegation visited in March 2024. (Image: Cyprus Police/fair use)

25 holding cells inside the station were reserved for individuals in so-called administrative detention - asylum seekers who were detained under the country’s refugee law.

Cypriot and EU law prohibit the arbitrary detention of asylum seekers. However, the ministry of interior is allowed to detain refugees under exceptional cases, such as protecting national security.

At the Lakatamia station, police officers spoke of what they call the “Syrian problem” - the challenge of deporting Syrians, who cannot be forcibly returned to their country. They can however choose to voluntarily return through Amman in Jordan or Beirut in Lebanon.

Frontex trains officers from the police’s Aliens and Immigration Unit to flag anyone who expresses a willingness to return during police interviews.

At the time of the delegation’s visit, eight asylum seekers were in detention, including five from Syria.

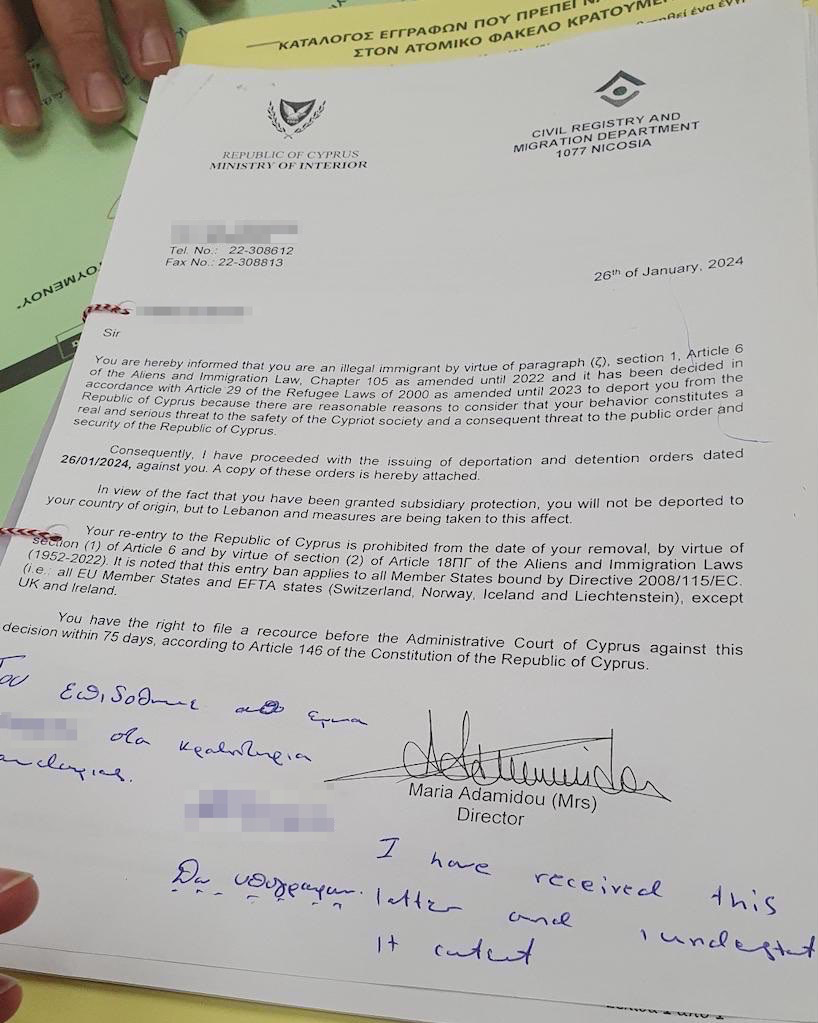

Fares*, one of the Syrian detainees, told the delegation that he had been detained for two months already. His detention order, which the delegation saw, claimed he was a “threat to the public order and security” of Cyprus. He was also issued with a deportation order to Lebanon, instead of Syria.

A picture taken of Fares’ deportation order to Lebanon, signed by the current director of the Migration Department within the newly formed Deputy Ministry of Migration. (Image: The New Arab)

At a later meeting, the delegation put Fares’ case to Andreas Georgiadis, the head of Cyprus’ Asylum Service.

Georgiadis said that detention orders for Syrians are usually issued in cases of serious crime. Even if deportation is not possible, such orders are used to extend detention, which has no time limit for asylum seekers.

Because the orders do not come from judicial officers, they sometimes lack the oversight that is afforded to regular suspects of crimes. The longest a Syrian asylum-seeker has been unlawfully detained for in Cyprus is two years, nine months and twelve days.

In the past, Cypriot authorities justified this type of detention by citing potential links to terrorism and using somewhat dubious evidence.

“No Syrian asylum seeker has ever been convicted for a terrorism-related crime [in Cyprus]” Corina Drousiotou, senior legal advisor at the Cyprus Refugee Council NGO, told TNA. “The evidence [in those cases] is very wishy-washy”, she added.

Human rights bodies have long decried the Cypriot authorities’ use of police holding cells for the detention of asylum seekers.

During a visit in May 2023, the Council of Europe’s Committee for the Prevention of Torture (CPT) found that asylum seekers in detention were treated almost the same way as criminal suspects. Some of them had been held in police stations for “excessive” periods of time, lasting for more than one year in few exceptional cases.

In the view of the Committee, “subjecting foreign nationals to appalling living conditions and regimes in reception centres and police stations... is contrary to European values and international human rights law.”

In July 2019, a group of 15 detainees, including nine Syrians, started a hunger strike inside the Menoyia centre, to protest their lengthy incarceration.

A look inside the Lakatamia Police holding cells. Asylum seekers reportedly filmed the original video in July 2012, while on hunger strike against protracted detention. (Image: nadiasyria, Youtube/fair use)

Between 2020 and 2023, the Supreme Court of Cyprus issued a series of Habeas Corpus decisions finding that some of these detentions - which lasted from 14 to 21 months - were unlawful. The authorities had also failed to investigate the alleged threats to national security used to justify their detention, just like in the case of Chazel’s co-detainees.

Nicoletta Charalambidou, a Nicosia-based human rights lawyer who represented the Syrian detainees in court, told TNA that authorities would visit the detainees on a monthly basis, encouraging them to sign up for voluntary returns.

“[Some of the detainees] were thinking about it. If it was not for the situation in Syria before the fall of Assad, people may have actually decided to ‘voluntarily return’”, said Charalambidou.

In one case, the Supreme Court reprimanded Cypriot and European authorities for their use of detention to force the deportation of Syrians

In the view of the Court, the authorities were clearly buying time, looking for third countries to deport the detainees to, while fully aware that Syria remained a war zone.

According to Charalambidou, the authorities are now targeting long-time Syrian residents in Cyprus instead.

The vast majority of Syrians in the country are not entitled to family reunification. The Cypriot lawyer told TNA that authorities interpret money transfers to relatives back home as facilitation of their smuggling.

In the last year alone, Charalambidou has had seven or eight cases in which authorities were arresting Syrians under dubious smuggling or terrorism charges, and detaining them for up to 12 months with the aim of deporting them. Fares’ case was one of them.

Meanwhile, for Syrians outside detention, a widespread worsening of their living conditions has pushed many to consider leaving.

Drousiotou, from the Cyprus Refugee Council, told TNA that “the conditions are so poor that people are being squeezed out [into] poverty.”

“We have had families of Syrians where the father is sending his wife and children back to Syria. And this is pre-November [i.e. before the fall of Assad], out of desperation, because they just can't afford to sustain themselves,” Drousiotou added.

Image taken of the security fence around Pournara, Cyprus’ main refugee reception centre, during a visit in September 2023. (Image: The New Arab)

Too many returns to oversee

Maria Stylianou-Lottides, the Cypriot Commissioner for the Protection of Human Rights, is mandated to monitor forced deportations for compliance with human rights, as required by EU law. According to her, no Syrian has ever been deported from detention.

However, due to the high number of deportation flights, her office simply does not have the capacity to oversee them all.

In 2024, the Commissioner monitored only 45 (32%) out of 141 deportation flights. According to their 2023 report, the police is partly responsible for the low rates of monitoring as it informs the commissioner of deportations only within 24 hours of the planned flight.

The commissioner added that they do not monitor voluntary returns conducted outside of detention, which are the ones that Syrians can sign up to.

To Drousiotou, the legal advisor at the Cyprus Refugee Council, the high number of unmonitored voluntary returns is concerning because it makes it difficult to identify "systemic practices”.

The UN Refugee agency (UNHCR) does have a presence on the island, but has been sidelined by the authorities.

According to Louise Donovan, senior communications officer at UNHCR, the agency has not been able to verify whether returns from Cyprus to Syria are truly safe and voluntary.

In the absence of proper oversight, Cyprus could be found in violation of the European Convention on Human Rights over its voluntary return programme.

The European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), which is in charge of upholding the Convention, has previously ruled that countries can be held liable for the outcomes of their coerced returns of asylum seekers - even if they were voluntary on paper.

In 2019, the ECtHR found that Finnish authorities could not absolve themselves of their responsibility in the assassination of an asylum seeker they deported back to Iraq, even though he signed off on a waiver as part of his return.

Such a waiver was invalid, in the view of the court, because the returnee did not have “a genuinely free choice”.

The ruling was invalidated in 2021, when Finnish authorities were able to demonstrate that the asylum seeker was still alive in Iraq and evidence related to his death had been forged.

Jean-Pierre Gauci, a senior research fellow at the British Institute of International and Comparative Law, wrote that “although the decision has since been annulled for factual reasons, the reasoning is nonetheless still persuasive”.

Enter Frontex

Cyprus has relied on the support of the European Border and Coast Guard Agency (Frontex) to bolster its return programmes - both forced and voluntary.

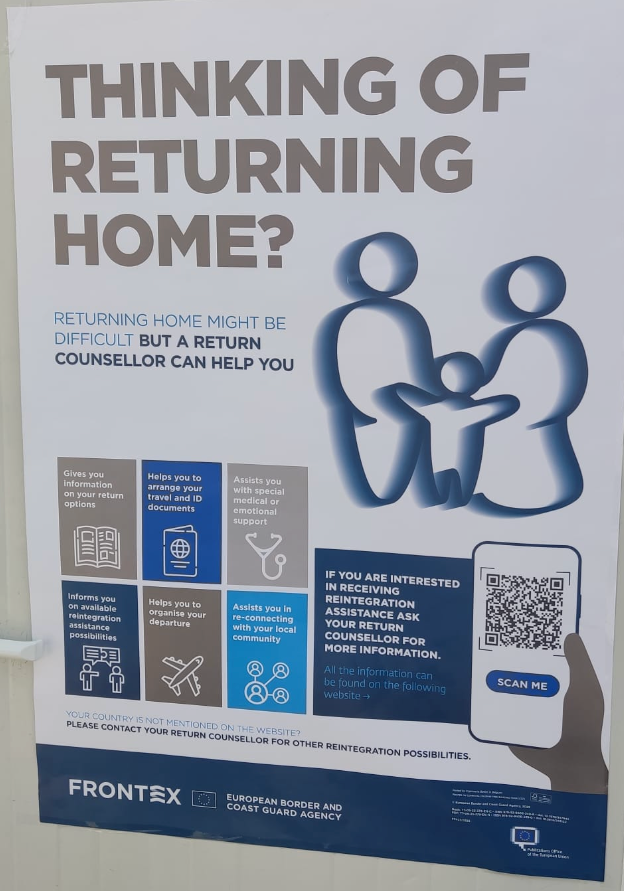

As return counsellors, Frontex officers inform people about “[the] obligation to leave the country and the consequences of not leaving”, as well as encouraging voluntary returns.

Entrance to the Pournara first reception centre, where Frontex counsellors are deployed to promote voluntary returns. Photo taken in March 2024. (Image: The New Arab)

The first Frontex counsellor arrived in Cyprus as early as March 2021. A spokesperson for Frontex told TNA that the agency deployed 11 return counsellors to Cyprus in 2023, where they conducted 6,806 counselling sessions to promote voluntary returns.

This suggests that Frontex’ officers interacted with more than half of all people who were received in Pournara that year. The overwhelming majority of Pournara’s residents were from Syria.

A poster on the door of Frontex’s office inside the Pournara camp in Cyprus. March 2024. (Image: The New Arab)

Frontex’ counsellors continued to promote voluntary returns to Syrians even after Cyprus imposed its hostile measures in April 2024. In the first ten months of the year, 5,487 counselling sessions were conducted by 12 Frontex officers in Cyprus.

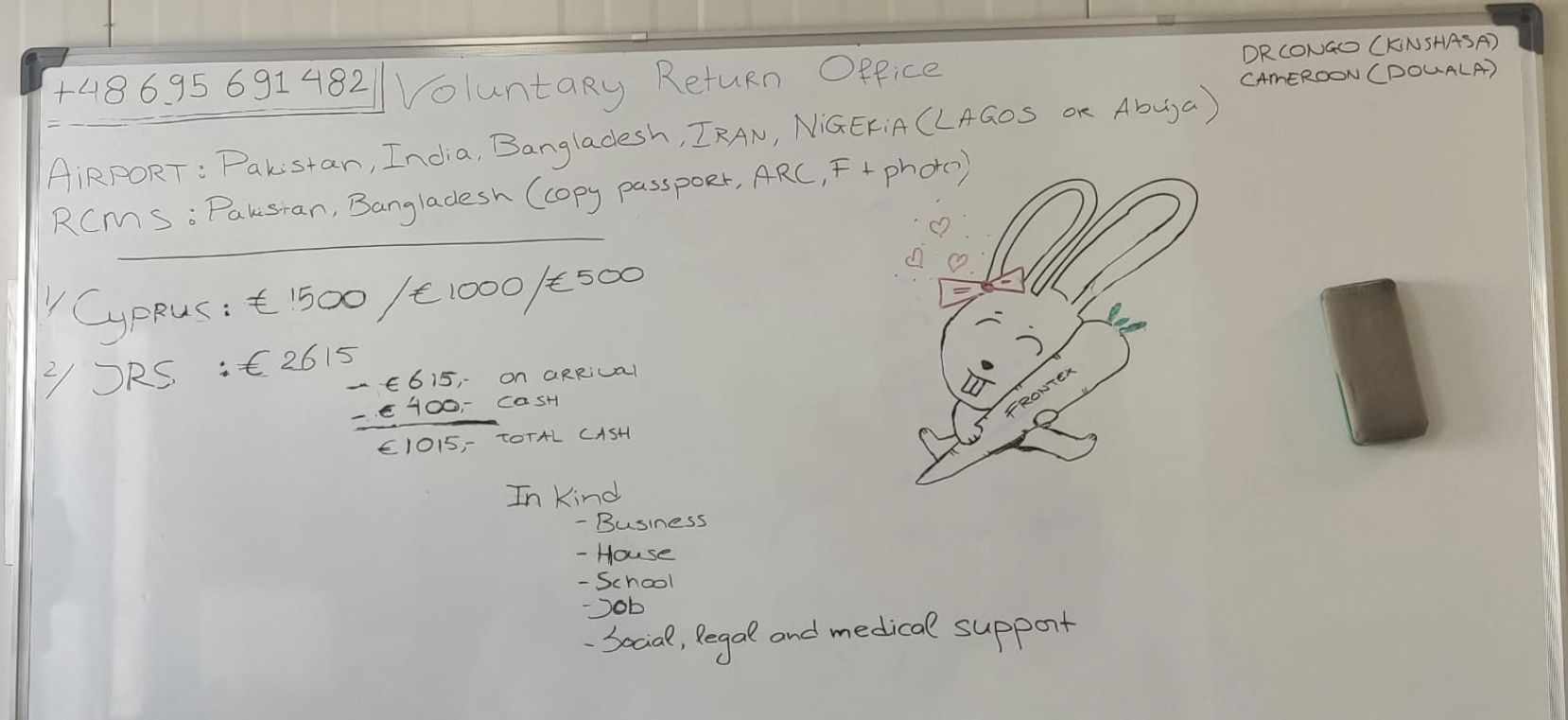

A whiteboard inside Frontex’ office in the Pournara camp, listing the financial incentives available for individuals agreeing to be deported from Cyprus. March 2024. (Image: The New Arab)

Frontex officers told the delegation that most asylum seekers prefer to sign up for Cyprus’ voluntary returns - as opposed to the Frontex-funded EU Reintegration Programme - because it allows them to receive a larger financial compensation right before they board their plane at the airport.

Unlike Frontex, Cyprus offers individuals from Syria, Iran and Afghanistan €1,000 to €1,500 as an incentive for their deportation. Asylum applications from these three countries represented 75% of all applications received in Cyprus in the first eleven months of 2024.

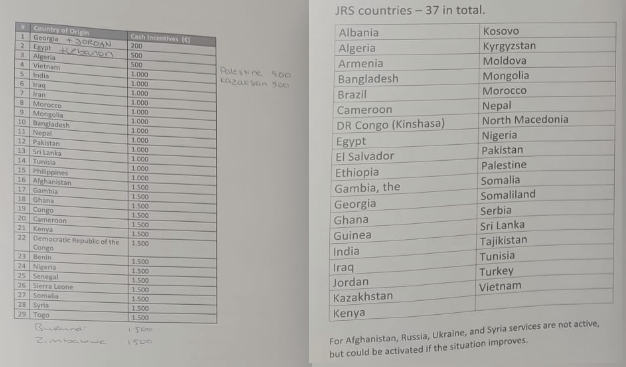

Lists of countries and financial incentives given for individuals who sign up for voluntary returns, through programs offered by Cyprus (left) and Frontex (right). Picture taken inside Frontex’s office in the Pournara Camp in March 2024. (Image: The New Arab)

A supercharged deportation machine

With Frontex’s help, the ministry of interior supercharged its returns program into a full-blown deportation machine.

A spokesperson for the agency justified its involvement by stating that, in 95% of the 2024 returns, “migrants decided to return voluntarily, without any force used.”

According to its Head Liaison Officer in Cyprus Gregoris Apostolis, Frontex is already trialing this model of cooperation in other EU states, including Bulgaria.

Deportations: New role for Frontex as EU pushes for more “voluntary” returns

The EU has been funding new accelerated asylum and deportation procedures in Bulgaria, including a new "assisted voluntary return" project. Increasing "voluntary" returns is a key part of the plan to increase deportations from the EU, with Frontex playing an increasing role. The project targets individuals in detention. Experts question whether such procedures can ever be truly voluntary.

Meanwhile, within Frontex, staff raised concerns with the way returns were being conducted.

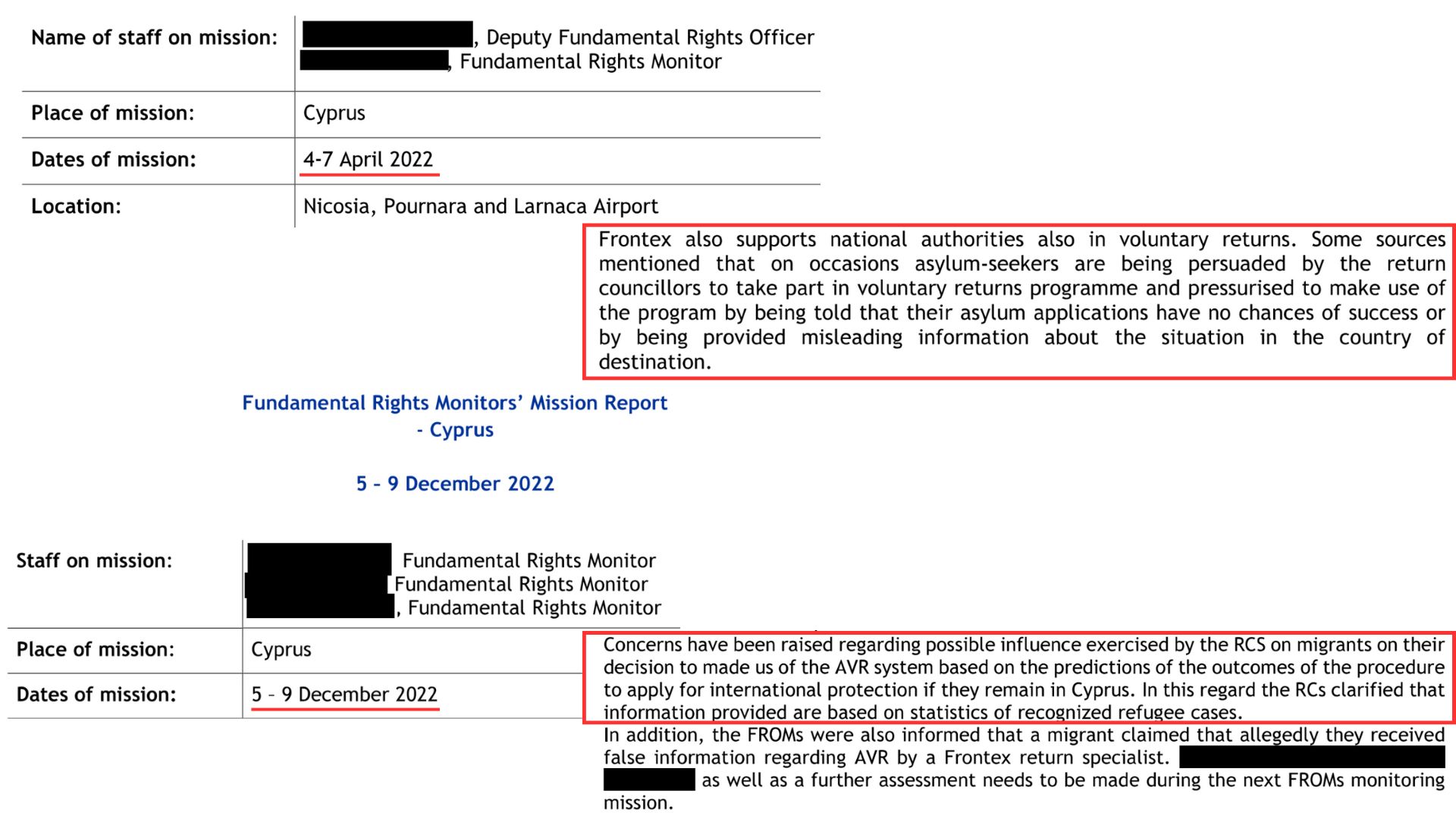

In April 2022, Frontex Fundamental Rights monitors began reporting instances of asylum seekers “pressured” to take part in voluntary returns, receiving misleading information on the situation in their country of return, and being told that their asylum applications had no chance of success.

Excerpts from reports by Frontex Fundamental Rights monitors after their visits to Cyprus in 2022. The reports mention instances of external pressure exerted on asylum seekers in Pournara to sign up for voluntary returns. (Image: Border Violence Monitoring Network)

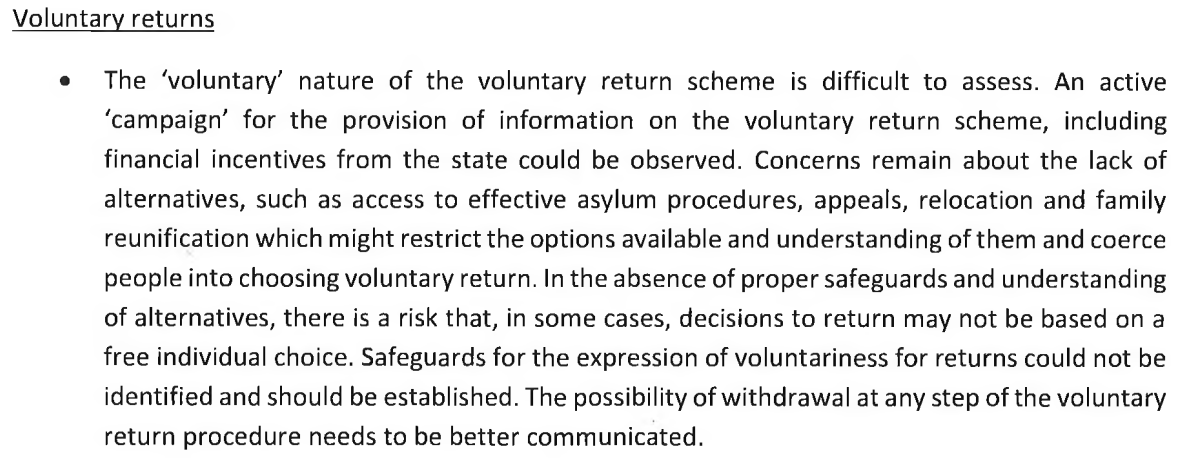

Frontex’ Consultative Forum (CF), an independent body within the agency in charge of safeguarding human rights, also had concerns with the “voluntary” nature of returns.

For Syrian asylum seekers especially, the forum reported in May 2024 that “it might be too soon and misleading” to promote voluntary returns to Syrians, given that access to asylum was suspended. It suggested that Frontex cease providing return counselling in Pournara altogether.

Excerpt from a report submitted by the Consultative Forum (CF) to Frontex’ Management board in May 2024, after a visit to Cyprus. (Image: The New Arab)

Frontex’ leadership did not heed their call. In an itemised response to the forum, Frontex Executive Director Hans Leijtens defended the agency’s activities in Cyprus.

According to him, Frontex’ return counsellors had to stay, as their departure would “negatively affect the information position of migrants”.

“The information position of migrants”

TNA obtained the copy of a WhatsApp conversation of an individual who approached the voluntary returns’ office inside Pournara for counselling.

In the chat exchange, conducted between 1 and 6 December 2024, a few days before Assad’s fall, Badr* asked the counsellors what kind of support Cypriot authorities could provide for his return as a Syrian in Cyprus back to Aleppo.

At the time, Syrian opposition groups had just retaken the city and were on their way to overthrowing the regime of Bashar al-Assad. In a message, Badr mentioned that his wife and children were stuck in Aleppo due to ongoing bombardments.

In response, one of the officers said that the Cypriot authorities would book him a flight directly to Amman, in Jordan, where he would then be able to take a bus to Damascus.

“From Damascus, you will need to figure it out on your own”, another officer added in a second voice message.

Missing from the information provided, however, was the fact that any journey from Damascus to Aleppo at the time would involve crossing the line of fighting between pro- and anti-Assad forces.

Officers tried to call Badr, potentially to discuss the situation in more detail, but did not reach him.

On 6 December, Jordanian authorities closed the Nasib border crossing with Syria. Badr asked the officers if that would affect his return in some way. He never received a reply.

TNA asked Aydan Iyigüngör, co-chair of Frontex’ Consultative Forum, what measures ought to be taken by the border agency when counselling a case like Badr’s.

Iyigüngör told us that, in an ideal scenario, the Frontex officer would create a Serious Incident Report (SIR). "Wherever there is a risk for a fundamental rights violation, there is an obligation to report it without delay," she said.

A spokesperson for Frontex said that no SIR was submitted for the voluntary returns of Syrians during the rebel offensive.

More EU money for coerced and ‘voluntary’ returns

While the European Commission (EC) has acknowledged the need for independent monitoring of the voluntary return of Syrians, it is failing to put its money where its mouth is.

The New Arab reviewed the projects that the EC has agreed to fund in Cyprus under its Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund for the period 2021-2027.

Of the €56.4 million ($58.4 million) it has paid to Cyprus from the fund, the Commission has allocated no money to monitor “voluntary” returns.

Between May 2022 and September 2024, the EC provided Cyprus with €9.7 million for its voluntary returns program - 90% of the program’s budget. For that amount, Cyprus deported some 12,600 individuals as “assisted voluntary returns” - about 1.3% of its population.

For the same period, the Commission allocated some €2 million for the forced returns of some 4,507 individuals from Cyprus.

Jeff Crisp, refugee and asylum expert at the University of Oxford, told TNA that “forced returns where people are actually handcuffed and put onto a plane and sent with security officers are much, much more expensive than if you can persuade somebody to get on the plane by themselves.”

A measly €121,547 was assigned by the EU to Cyprus' Commissioner for the Protection of Human Rights to monitor forced deportations between July 2022 and December 2027.

The European Commission is now also financing the construction of new facilities to detain asylum seekers, with the aim of deporting them.

In June 2024, it announced the allocation of some €67.7 million for Limnes, a €84.9 million complex due to be completed in 2025, which will include a “specialised Detention Centre for returns” and a reception centre.

The detention centre will hold up to 800 individuals who have received a deportation order, including those for whom the order cannot be executed. Limnes is set to increase sevenfold Cyprus’ capacity to coerce people like Fares to return.

The Limnes pre-removal & detention centre, as seen during a visit in March 2023. Once completed, it will increase Cyprus’ migrant detention capacity by 800 units. (Image: The New Arab)

In October 2024, Italy and Austria called on the EU to declare parts of Syria safe for deportations. The European Commission then announced a €25 million fund for “new models for incentivising assisted voluntary returns.” It is targeted at Mediterranean countries "whose return systems are under pressure."

The announcement specifically singled out Cyprus’ voluntary returns as a successful model that could benefit from more resources.

Up to 30% of the money granted to beneficiary states could be used as compensation for individuals who choose to “cooperate” rather than being deported by direct force.

The New Arab asked the Commission if additional funding had been allocated to Cyprus’ returns program under this new fund. No reply was received in time for publication.

A one-way ticket back to Syria

Shortly after we spoke in December 2024, Abu Iskander Alshami, the Damascene living in Cyprus, posted images documenting the return of a Syrian national on a 35,000-member strong Facebook page he runs.

Images posted on Facebook of an individual receiving €1,500 and a one-way ticket from Cyprus to Jordan on 26 December 2024, as part of the country’s voluntary returns programme. (The Arabs’ Guide to Cyprus, Facebook/fair use)

For Syrians like Alshami, the choice to return is far from voluntary - our investigation has shown it is shaped by hostile state practices that want to dispose of asylum seekers as inexpensively as possible.

As policymakers in Brussels applaud Cyprus’ supposedly successful voluntary return program and look to expand it across member states, Syrians are once again left to pay a hefty price for policies that prioritise exclusion over protection.

*The names of these individuals were changed to protect their identity.

Editor's note: This story was edited on 18 February 2019 to make a correction. The initial version suggested that the 2019 decision by the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) against Finland was still valid. The text has been amended to reflect the fact that the ECtHR invalidated its ruling in July 2021.

-----

Additional reporting support: Clara Zinecker.

Editing and fact-checking: The New Arab Investigative Editor Andrea Glioti

For questions, comments and complaints please email Andrea Glioti andrea.glioti [at] newarab.com or Anas Ambri anas.ambri [at] newarab.com.

Sensitive info and tips are to be sent via encrypted email to thenewarab [at] tutanota.com and/or secure [at] statewatch.org (PGP key)

Our work is only possible with your support.

Become a Friend of Statewatch from as little as £1/€1 per month.

Further reading

Polish government proposes life-long EU entry bans for deportees

In the coming months, EU institutions will start negotiating a new law to increase deportations. EU governments want their positions taken into account in the European Commission’s forthcoming proposal. The Polish government has proposed banning deportees from EU territory for “an indefinite period of time,” alongside other coercive measures.

Deportations: New role for Frontex as EU pushes for more “voluntary” returns

A special report by Hope Barker and Anas Ambri: The EU has been funding new accelerated asylum and deportation procedures in Bulgaria, including a new "assisted voluntary return" project. Increasing "voluntary" returns is a key part of the plan to increase deportations from the EU, with Frontex playing an increasing role. The project targets individuals in detention. Experts question whether such procedures can ever be truly voluntary.

Frontex’s increasing role in reintegration policy and its effects in West Africa

The externalisation of European border controls to Africa has received substantial political and critical attention. The same cannot be said of “reintegration” policies, ostensibly designed to support people deported from the EU. Frontex’s role in both deportation and reintegration is increasing. The consequences of this in The Gambia and Nigeria raise questions over national sovereignty, the rights of and support for deportees, and the instrumentalisation of independent organisations.

Spotted an error? If you've spotted a problem with this page, just click once to let us know.