From Cutro to Pylos: what two shipwrecks reveal about Europe’s deadly migration policies

Topic

22 May 2024

The anniversary of the shipwreck in Crotone on 26 February was marked by relatives and supporters of at least 94 people who died on the morning of that same day in 2023. They gathered on the beach in Cutro, in the city of Milan, and elsewhere in Italy: the names of the dead were read at public events, and survivors gave their testimonies.Three months later, it will also be the first anniversary of the Pylos shipwreck, in which at least 500 people lost their lives, and similar events will mark that anniversary. [1]

Support our work: become a Friend of Statewatch from as little as £1/€1 per month.

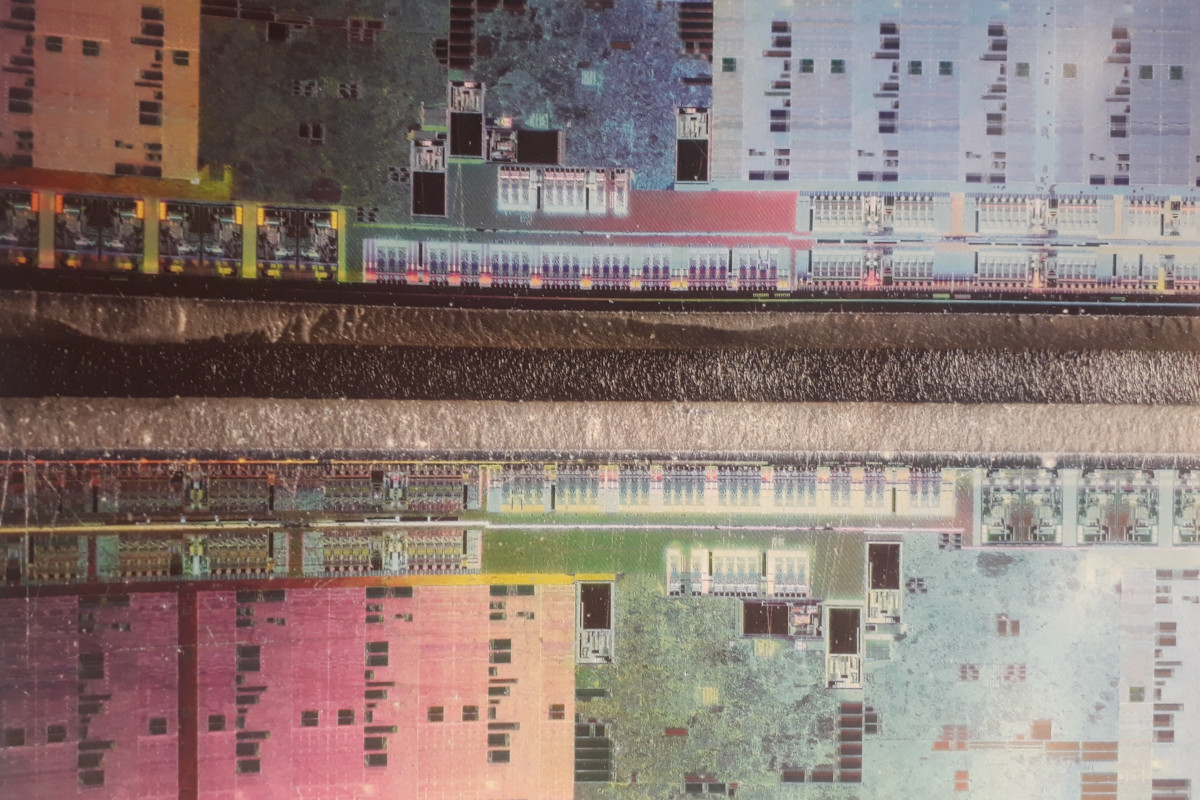

Giuseppe Murabito: The Sound of Silence - Relitto della Maddalena Lofaro o Rigoletto, CC BY-SA 2.0

Giuseppe Murabito: The Sound of Silence - Relitto della Maddalena Lofaro o Rigoletto, CC BY-SA 2.0

In the year after the Crotone shipwreck and several months since Pylos, there have been a number of developments of which it is necessary to take stock. These are far from the only migrant shipwrecks that occurred at that time. The International Organization for Migration (IOM) estimates that in 2023, the number of fatalities in the Mediterranean reached 3,129, with an additional 537 fatalities on the West Africa Atlantic route to the Canary islands. [2] What is nevertheless striking about the Crotone and Pylos cases is how they illuminate the deadly nature of the EU’s border policies.

In both cases, blame for the shipwrecks has been assigned to survivors who allegedly piloted the vessels and who are now facing prosecution. [3] However, it is also apparent that both Greece and Italy failed to uphold their search and rescue (SAR) duties. Furthermore, despite Frontex bearing “coast guard” in its current name, the European Ombudsman’s inquiry highlights that it is a misnomer, as it does not have powers to fulfill that role without national authorities’ assistance. [4] While this partly shifts blame away from the agency, it fails to mitigate concern over its strategic endeavors and their effects to date. Both cases echo earlier ones (in particular, a case in Malta and others in Greece), [5] and show that it is the EU’s policies of deterrence and deflection that are ultimately at fault.

Prosecution of survivors

On 7 February 2024, a 29 year-old Turkish man, Gun Ufuk, was convicted and sentenced to 20 years’ imprisonment in Crotone (Calabria, Italy) under a fast-track procedure, while three other suspects are on trial facing the same charges of causing a shipwreck, facilitating illegal migration and causing death as an outcome of other criminal offences. [6] Similar dynamics seem to be at play in the Pylos case, where nine Egyptian survivors of the shipwreck (the “Pylos 9”) are under investigation and face charges of causing the shipwreck, facilitating unauthorised entry and membership of a criminal organisation. The Legal Centre Lesvos is representing two of the nine defendants:

“As LCL, we demand that the 9 accused of the Pylos shipwreck be immediately released and provided with appropriate psycho-social support as survivors of a deadly shipwreck. Charges against them should be dropped and an independent investigation should be carried out to investigate the circumstances of the shipwreck and determine the responsibilities and involvement of the Greek authorities and Frontex in the capsizing of the Adriana in light of their obligations to rescue and protect the lives of those on board.” [7]

Search and rescue failures

In the background were concerns about why two EU member states (Italy and Greece) and their respective coast guards had failed to conduct SAR missions that may have prevented loss of life - despite receiving timely information, aerial photographs and footage about the imperiled vessels from Frontex aerial surveillance aircraft.

In both cases, buck-passing has been prominent, and Frontex stressed that it provided adequate information to national authorities to prevent the shipwrecks whereas national authorities replied that the information received did not amount to a “mayday” call to prompt them into immediate action. [8]

It should be noted that, since the downscaling of EU SAR presence at sea in the central Mediterranean after 2015, efforts have been made both to subordinate rescue duties and a duty of care for vulnerable subjects to the policing of “irregular” migration, registration, investigations and post-disembarkation interviews. [9] Authorities have also sought to limit the reasons for which cases should automatically be considered as needing SAR interventions (see below).

The European Ombudsman’s inquiry

In February 2024, the European Ombudsman, Emily O’Reilly, concluded her inquiry into the Pylos shipwreck in which over 600 people died on 27 February 2023, calling for “changes to EU search and rescue rules and a public inquiry into deaths in the Mediterranean.” [10] Key issues raised in her report include the Greek coast guard’s failure to promptly initiate a rescue mission and Greek authorities’ refusal of offers of assistance from Frontex, preventing scrutiny of what was happening from above:

“Frontex made four separate offers to assist the Greek authorities by providing aerial surveillance of the Adriana but received no response. The current rules mean that Frontex was not permitted to go to the Adriana’s location at critical periods without the Greek authorities’ permission.”

The report is peppered with damning statements that may surprise people who have not paid close attention to developments in the immigration policy field. O’Reilly noted that Frontex “should consider whether the threshold has been reached to allow it to formally end its activities with the Member State in question,” calls for which it has resisted to date. She also highlighted that the agency’s mandate does not match its name, which includes the terms “coast guard”, due to its reliance on national authorities.

This would appear to be a call for the legislators to enhance Frontex’s SAR and coast guard role and capabilities, and the timing is noteworthy: the European Commission recently-published its first evaluation of Frontex’s 2019 Regulation, which was later examined by the Justice and Home Affairs Council.

O’Reilly also highlighted the “obvious tension between Frontex’s fundamental rights obligations and its duty to support Member States in border management control.” This root problem is not unrelated to the ideological role played by Frontex to date, in consistently pushing for tough border control measures as if they were of existential importance. In particular, its risk analysis assessment that SAR operations may amount to a “pull factor” was key to downscaling and retreating the presence of EU rescue vessels in the Mediterranean. At the same time, the tension between formal and operative levels was revealed by a choice to disregard human rights conditions in a third country like Libya that the EU formally acknowledges as being unsafe for migrants, whilst enhancing its rescue capabilities and contributing to establishing a Lybian SAR zone. [11] Further, a policy choice to make sea crossings more dangerous to undermine the traffickers’ business model was made under the 2015 Agenda on Migration (including in the 2015 EU Action Plan against migrant smuggling, quoted below) and later served as a reference for Italy’s efforts to criminalise civilian SAR operations:

““The Agenda set the goal to transform migrant smuggling networks from ‘low risk, high return’ operations into ‘high risk, low return’ ones”. [12]

From Cutro to Pylos: two shipwrecks, hundreds dead, two member states and an EU agency

The Cutro and Pylos shipwrecks occurred despite advanced knowledge of the situation from a combination of Frontex aerial surveillance and NGO alerts transmitted to responsible state authorities. The estimated number of victims in the two incidents was above 94 in the first case and up to 600 in the second one. The dynamics of the two cases were different, but they share a link to EU and member state efforts to reduce irregular border crossings by sea, at any cost.

Days after the shipwreck, on 9 March, a cabinet meeting was held by the Italian government in Cutro, followed by a press conference [13] during which murmurs among the press cohort arose due to inaccuracies in PM Meloni’s reconstruction, eliciting a response that sounded threatening:

“Are you trying to say that someone deliberately wanted these people to die?”

The Cutro decree was approved to toughen measures against so-called “irregular migration” and the leitmotif appeared to be that, apart from smugglers/traffickers (who must be hunted down worldwide, said Meloni), the victims only had themselves to blame, as the problem was their “vocation for leaving.” This is how Italian interior minister Piantedosi put it.

Piantedosi was on the staff of former Italian interior minister Matteo Salvini when a tug-of-war over sea rescues (including actions of dubious legality) occurred during the short-lived Five Star Movement/Lega Nord government in 2018-2019, [14] and he authored the January 2023 law decree that has resulted in several civilian SAR vessels being blocked and fined after the Meloni government took office.

Frontex exonerated itself from blame by highlighting how it had informed relevant authorities in timely fashion (submitting photographic evidence) and due to the presence of Italian representatives in its situation room in Warsaw, but this reading withstands scrutiny only up to a point, in light of evidence from the OLAF anti-corruption agency’s investigation into the EU agency.

The OLAF report (finalised in February 2021) was only made public by German NGO Frag den Staat in October 2022, [15] despite numerous previous requests for access, also from MEPs. However, the report’s content did not lead to appropriate action being taken to tackle irregularities enacted by member states in the realm of border control and sea crossings that are becoming routine. In particular, there was a case in which irregular manoeuvres and delayed rescue at sea by Maltese authorities in 2020 (several such cases involving Greece were also reported) that led to deaths and returns to Libya (see below) was unduly downgraded despite amounting to a serious case involving human rights violations.

Nonetheless, the resignation in April 2022 of the Frontex executive director, Fabrice Leggeri, was partly motivated by the report’s findings, which provided evidence that the direction in which the border agency was moving raised problems. In the case of both shipwrecks, Italian and Greek authorities squarely blamed traffickers and the migrants themselves, for attempting unsafe sea crossings. This was despite evidence that questions needed answering about how events unfolded and why search-and-rescue procedures that should be standard were not followed. The statements as well as legislative and investigative responses that followed deserve scrutiny, particularly regarding the Cutro decree adopted in Italy, intense pressure against NGOs in Greece and both states’ efforts to blame people who were on board (suspected of steering the vessels) for the tragedies.

Despite the court cases initiated against survivors and a conviction referred to above, investigations into both countries’ SAR failures are due. In Italy, an inquiry into six coast guard officers is underway concerning omission of rescue and culpable disaster for not having intervened and launched a search mission despite notification of its situation by Frontex’s Eagle 1 aircraft, and despite the bad weather at sea, as reported by Internazionale. [16] Nonetheless, it appears that political decision-making and the primacy assigned to the interior ministry (rather than the infrastructures ministry which is responsible for SAR activities) may have played a role.

Ombudswoman O’Reilly’s report on the Pylos case notes that the Greek ombudsman is investigating the case (investigation launched on 8 November 2023), among other investigations:

“The Hellenic Coast Guard (HCG) was present at the coordinates of the Adriana at the time. In the immediate aftermath of the incident, questions were raised about how the HCG conducted its response to the maritime emergency, including allegations that its actions may have contributed to the capsizing. There are different national investigations into the role of the HCG, including an ongoing inquiry by the Greek ombudsman, opened after the HCG decided not to launch its own internal disciplinary investigation. However, questions were also raised about the role of Frontex.” [17]

Cutro: SAR operations subordinated to policing

The shipwreck in Cutro occurred months after an Italian coalition government led by Giorgia Meloni of the right-wing Fratelli d’Italia party took office in October 2022. The tragedy was preceded by the umpteenth law decree [18] adopted by Italy to obstruct civilian sea rescue missions. Hence, the government’s primary concern was to clarify that the shipwreck was unrelated to the new measures, an easy task because the shipwreck happened in the Ionian Sea rather than in the waters off the north African coast where NGO vessels are sometimes present. [19]

However, this line of defence soon crumbled when other tragedies off the north African coasts unfolded in later weeks in areas that civilian sea rescue NGOs were being kept away from through obstructive tactics like assigning distant ports of safety in which to disembark people (contravening the law of the sea), temporarily blocking them and issuing administrative fines. It also turned out that Frontex’s warning of the sighting of a vessel in peril led Italy to launch a police operation against irregular migration instead of a rescue mission.

In fact, a customs and excise police (Guardia di Finanza, GdF) vessel set out to reach the Summer Love, but was forced to return due to rough sea conditions which the coast guard would have been better equipped to deal with. This behaviour reflects efforts over the last few years to limit cases to be dealt with through SAR missions, considering elements like the way in which vessels appear to be floating at sea, to seek to deem them as not in danger.

Pylos: sea borders treated as though they were solid, towing manoeuvres

The shipwreck of the Adriana fishing boat carrying over 700 passengers on the night of 13/14 June 2023 was the umpteenth case in which large-scale deaths resulted from unlawful procedures at sea by member state authorities that are becoming commonplace. In the first place, like in the Cutro shipwreck, declaration of a state of distress for the vessel requiring the launch of a SAR operation to save lives at sea was delayed. Moreover, it appears that an attempt to tow the Adriana preceded the moment when it sank in waters to the south west of Pylos. Solomon reported on the Frontex FRO’s internal report into the Adriana incident, which included criticism of the Hellenic Coast Guard (HCG) on various grounds:

- inaccurate reconstruction of events;

- ignoring Frontex offers of assistance;

- the rescue operation was launched when it was too late to save all the migrants, with an assistance request sent after the vessel sank (considering that inadequate resources of its own were deployed and in the area);

- survivors’ accounts to Frontex interviewers were deemed “consistent” and stated that the vessel had been towed, leading to it sinking; and

- the HCG’s refusal to answer questions posed to it by Frontex. [20]

Notions referred to above as instrumental justifications for state authorities not to launch SAR missions (which would technically preclude returns to third countries) applied, considering that:

“In the days following the wreck, the Hellenic Coast Guard maintained that the Adriana was seaworthy and had been drifting (without speed) for only a short time.”

The Frontex report notes that this disagrees with survivors’ testimonies as well as sea traffic data.

The Maltese/Libyan precedent: justice denied

The Adriana case was reminiscent of a case (that of the April 2020 Easter Monday tragedy) reported in the aforementioned OLAF report into Frontex, [21] which lamented the downgrading of a serious incident report (apparently by Leggeri himself) involving the apparent towing of a vessel by Maltese vessels towards Italian waters to relinquish SAR responsibilities. It appeared that this move sought to avoid involving the Frontex Fundamental Rights Officer in the case (sometimes referred to in the agency’s higher echelons as “Pol Pot”) and to avert a diplomatic incident involving Malta, Frontex and Italy. Had Malta been duly identified and reprimanded for violating maritime law to delay a rescue causing deaths, acting disloyally towards a fellow member state (Italy) and engineering an operation whereby a private fishing vessel returned the survivors to Libya (12 died, 53 were returned), Greek authorities may have hesitated before delaying a necessary rescue.

The above operation was coordinated by Neville Gafà, previously on PM Muscat’s staff (see previous Statewatch coverage [22] here) and asked by his successor Abela’s government to take charge in this case and admitted using a similar approach between July 2018 and January 2020. Not only did Gafà boast about his role in the pushback, Malta also signed its own memorandum of understanding (MoU) with Libya in May 2020 after this incident, following the Italian example which has drawn plentiful criticism. Three years later, the Times of Malta was perplexed by the denial of documents that were listed as annexes to the MoU, when the reply to a freedom of information request submitted, was that “no annexes exist”.[23]

On 6 March 2024, a case brought by 50 survivors and two relatives of the victims of the 2020 Easter Monday tragedy was shelved in Malta as a result of a technicality regarding the appointment of the plaintiffs’ legal counsel. [24] Their case had claimed that the decision to push them back to Libya violated human rights under the Maltese Constitution, the European Convention on Human Rights and the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights because Libya was not to be considered a safe country.

Leijtens follows Leggeri’s example

On 5 March 2024, in response to the Ombudsman’s report, Frontex executive director Hans Leijtens followed up on what had been a welcome case in which Frontex had finally identified and publicly reported shortcomings by national authorities in relation to delayed sea rescues by mimicking his predecessor. He questioned the Ombudswoman’s findings on three grounds. [25]

First, he supported the view according to which “the simple fact that it [a vessel] is crowded does not qualify it as a distress case”, which is particularly offensive in the context of the Pylos and Cutro cases. Second, he confirmed that communications with the Libyan coast guard would continue (despite repeated findings by courts that the country cannot be considered a safe place for disembarkation of rescued people). Thirdly, he noted that Frontex is not equipped to undertake search and rescue activities, disregarding the fact that its risk analysis reports were behind the retreat and withdrawal of EU rescue assets from the sea after 2015, when efficient sea rescues were identified as being liable to amount to a “pull factor”. This was because EU vessels conducting rescues were forbidden from returning people to Libya, whereas disembarkation in EU ports would mean a rise in “irregular border crossings” and asylum applications, lowering both of which feature among the agency’s strategic goals alongside increasing deportations (returns in official speak).

In fact, when naval vessels deployed in security operations (like EUNAVFOR MED Operation Irini) enact sea rescues, they now file reports to certify that their rescue operations do not amount to a “pull factor”. In fact, the decision confirming the operation’s deployment from 31 March 2022 to 31 March 2023 (subject to reconfirmations) for the period from 1 August to 30 November 2022, states that:

“(2) Article 8(3) of Decision (CFSP) 2020/472 provides that, notwithstanding that period, the authorisation of the operation is to be reconfirmed every four months and that the Political and Security Committee is to prolong the operation unless the deployment of maritime assets of the operation produces a pull effect on migration on the basis of substantiated evidence gathered according to the criteria set out in the Operations Plan.” [26]

In another claim that echoes Leggeri’s behaviour when he stated upon resignation that Frontex is a border control agency rather than a human rights body, Leijtens stated that “We are not the European Search and Rescue Agency. We are the European Border and Coast Guard Agency.” [27] It should also be noted that Leggeri has unsurprisingly (considering his conduct as Frontex executive Director) announced that he will run in the European Parliament elections for Marine Le Pen’s Rassemblement National party in France.

Latest developments

NGO aircraft Mediterranean flight ban in Italy

On 6 May 2024, the Italian civil aviation authority ENAC (which reports to the transport and infrastructures ministry headed by Matteo Salvini) issued five orders banning civilian SAR NGO aircraft (and vessels) from monitoring events in the central Mediterranean. [28] The orders relate to five Sicilian airports (Lampedusa, Pantelleria, Palermo Punta Raisi and Bocca di Falco, Trapani Birgi) and bear the title “Irregular migratory phenomenon by sea arriving from the north African coast. Prohibition of the operativity of NGO aircraft and vessels on the scene of the central Mediterranean”, an order that came into force “immediately” (article 2, “Fenomeno migratorio irregolare via mare proveniente dalle coste dell’Africa del nord. Interdizione all’operatività dei velivoli e delle imbarcazioni delle ONG sullo scenario del Mare Mediterraneo centrale”). Article 1 (the basic measure) suggests that sanctions under the code of navigation including the administrative blocking of vehicles may be applied for undertaking SAR activities outside of the current normative framework, disregarding past cooperation between NGO vessels and the Italian MRCC and coastguard.

Worse, beyond asserting the exclusive SAR competences of the Italian Coast Guard authority, the explanatory statements to justify an unusual measure insidiously suggest that the NGO vessels and aircraft “unduly” intervened at sea and that such undue actions may endanger the physical health of migrants “not assisted according to the protocols that are in force which have been approved by the maritime authority”.

Sea-Watch responded by noting that the order was unlawful and sought to conceal rights violations at sea, undertaking a monitoring flight two days later. [29] The jurist, lawyer and academic Fulvio Vassallo Paleologo explained [30] that there is a lack of legal basis in the orders, which amount to allowing ample margins of discretion to the infrastructures ministry as regards sanctions and possible fines and/or administrative stops. Moreover, the National Authority of Civil Aviation (ENAC) has acted beyond its competences and powers, because the international normative framework referred to does not authorise prohibitions of necessary search and rescue activities, also because their spotting work has sometimes resulted in Italian Maritime Rescue Coordination Centre-led rescue operations.

Charges against the Pylos 9 dismissed

On 21 May 2024, the criminal court in Kalamata dismissed the charges against nine Egyptians accused of smuggling and facilitating illegal entry in relation to the Pylos shipwreck, declaring itself incompetent to adjudicate charges of membership of a criminal organisation. The decision results from a claim by the defence that the court lacked juridisdiction because the incident happened in international waters, as reported by the Legal Centre Lesvos. [30] Dismissal of the charges on this technical ground prevented scrutiny of substantive aspects of the case linked to the intervention of the Greek coast guard and manoeuvres (including a claimed towing attempt) that may have played a part in the outcome. Two Hellenic Coast Guard officers (including the captain of HCG Vessel 920) were also questioned, but their involvement was limited to establishing the location of their intervention, rather than delving into their acts and possible omissions.

The Legal Centre Lesvos statement concluded:

“The Pylos 9 defendants, who were facing several life sentences, will now be released from prison. While today’s outcome comes as a great relief, in particular knowing the context of systematic criminalisation of migrants in Greece, it is important not to forget the ordeal endured by the nine accused, themselves survivors of the shipwreck, who despite having claimed their innocence from the outset were nevertheless prosecuted and detained nearly a year, without access to psycho-social support.”

Yasha Maccanico

Sources

[1]Pressenza, 26.2.2024, Cutro un anno dopo. Mai più morti in mare, https://www.pressenza.com/it/2024/02/cutro-un-anno-dopo-mai-piu-morti-in-mare/ ; Pressenza, 25.2.2024, Milano abbraccia Cutro, https://www.pressenza.com/it/2024/02/milano-abbraccia-cutro/ ; Pressenza, 1.3.2024, Cutro, un anno dopo. Andare oltre l’accoglienza, https://www.pressenza.com/it/2024/03/cutro-un-anno-dopo-andare-oltre-laccoglienza/ ; Memoria Mediterranea (MemMed), Report, “Naufragio di Cutro, a un mese dalla strage di Stato. Resoconto del progetto Mem.Med”, https://memoriamediterranea.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Naufragio-di-Cutro.pdf and Memoirs of people killed by borders, https://memoriamediterranea.org/en/memoirs/

[2] IOM, Missing Migrants Project infosheets, https://missingmigrants.iom.int/region/mediterranean ; https://missingmigrants.iom.int/region/africa?

[3] Altreconomia, Cutro, una distanza incolmabile. Il reportage nel primo anniversario della strage, 27.2.2024, https://altreconomia.it/cutro-una-distanza-incolmabile-il-reportage-nel-primo-anniversario-della-strage/

[4] European Ombudsman, Decision on how the European Border and Coast Guard Agency (Frontex) complies with its fundamental rights obligations with regard to search and rescue in the context of its maritime surveillance activities, in particular the Adriana shipwreck (OI/3/2023/MHZ), 26.2.2024, https://www.ombudsman.europa.eu/en/press-release/en/182676

[5] FragdenStaat, OLAF Final Report on Frontex, CASE No OC/2021/0451/A1, October 2022, https://fragdenstaat.de/dokumente/23397 -olaf-final-report-on-frontex/, https://fragdenstaat.de/en/blog/2022/10/13/frontex-olaf-report-leaked/

[6] Internazionale, A. Camilli, 23.2.2024, “Un anno dopo Cutro l’accoglienza è stata smantellata”, https://www.internazionale.it/reportage/annalisa-camilli/2024/02/23/un-anno-dopo-cutro-accoglienza-smantellata

[7] Legal Centre Lesvos, LCL lawyers take over defence of 2 survivors accused of the Adriana shipwreck, 16.10.2023, https://legalcentrelesvos.org/2023/10/16/lcl-lawyers-take-over-the-defence-of-2-survivors-accused-of-the-adriana-shipwreck/

[8] Solomon, “It was already too late”: Frontex blames the Hellenic Coast Guard for the Pylos shipwreck, 1.2.2024, https://wearesolomon.com/mag/format/feature/it-was-already-too-late-frontex-blames-the-hellenic-coast-guard-for-the-pylos-shipwreck/

[9] SOS Mediterranee press statement, 6.12.2023, “Decreto Piantedosi: le Ong pagano il prezzo del disinteresse per il diritto marittimo”, https://sosmediterranee.it/focus-sul-decreto-piantedosi-le-ong-pagano-il-prezzo-del-disinteresse-per-il-diritto-marittimo/

[10] European Ombudsman, Decision on how the European Border and Coast Guard Agency (Frontex) complies with its fundamental rights obligations with regard to search and rescue in the context of its maritime surveillance activities, in particular the Adriana shipwreck (OI/3/2023/MHZ), 26.2.2024, https://www.ombudsman.europa.eu/en/press-release/en/182676

[11] Statewatch, Italy renews Memorandum with Libya, as evidence of a secret Malta-Libya deal surfaces, March 2020, https://www.statewatch.org/analyses/2020/italy-renews-memorandum-with-libya-as-evidence-of-a-secret-malta-libya-deal-surfaces/

Statewatch, Malta-Libya Memorandum of Understanding, June 2020, https://www.statewatch.org/media/documents/news/2020/jun/malta-libya-mou-immigration.pdf

[12] EU Action Plan against migrant smuggling, COM(2015)285 final, 27 May 2015, https://ec.europa.eu/anti- trafficking/sites/antitrafficking/files/eu_action_plan_against_migrant_smuggling_en.pdf ; Statewatch, The Commission and Italy tie themselves up in knots over Libya, June 2019, https://www.statewatch.org/analyses/2019/the-commission-and-italy-tie-themselves-up-in-knots-over-libya/

[13] Conferenza stampa del Consiglio dei Ministri n. 24 a Cutro, 9.3.2023, https://www.youtube.com/live/51uHPKrCYX4

[14] Statewatch, Italy’s redefinition of sea rescue as a crime draws on EU policy for inspiration, April 2019, http://www.statewatch.org/media/documents/analyses/no-341-italy-salvini-boats-directive.pdf ; Cutro decree, decreto-legge 10 marzo 2023, n.20, “Disposizioni urgenti in materia di flussi di ingresso legale dei lavoratori stranieri e di prevenzione e contrasto all'immigrazione irregolare”; decreto-legge 5 ottobre 2023, n. 133 reca misure urgenti in materia di immigrazione e protezione internazionale, e per il supporto alle politiche di sicurezza e la funzionalità del Ministero dell'interno”.

[15] FragdenStaat, OLAF Final Report on Frontex, CASE No OC/2021/0451/A1, October 2022, https://fragdenstaat.de/dokumente/23397 -olaf-final-report-on-frontex/

https://fragdenstaat.de/en/blog/2022/10/13/frontex-olaf-report-leaked/

[16] Internazionale, A. Camilli, 23.2.2024, “Un anno dopo Cutro l’accoglienza è stata smantellata”, https://www.internazionale.it/reportage/annalisa-camilli/2024/02/23/un-anno-dopo-cutro-accoglienza-smantellata

[17] European Ombudsman, Decision on how the European Border and Coast Guard Agency (Frontex) complies with its fundamental rights obligations with regard to search and rescue in the context of its maritime surveillance activities, in particular the Adriana shipwreck (OI/3/2023/MHZ), 26.2.2024, https://www.ombudsman.europa.eu/en/press-release/en/182676

[18] Relatively recent measures include: Salvini decree, Decreto-legge, 4 October 2018, n. 113, “Disposizioni urgenti in materia di protezione internazionale e immigrazione, sicurezza pubblica, nonchè misure per la funzionalità del Ministero dell'interno e l'organizzazione e il funzionamento dell'Agenzia nazionale per l'amministrazione e la destinazione dei beni sequestrati e confiscati alla criminalità organizzata”; Directive no. 14100/141(8), March 2019, “Direttiva per il coordinamento unificato di attività di sorveglianza delle frontiere marittime e per il contrasto all’immigrazione illegale ex articolo 11 del d.lgs. 286/1998 recante il Testo Unico in materia di Immigrazione”; Piantedosi decree, Decreto legge n.1 del 2023, convertito con modificazioni dalla L. 24 febbraio 2023, n. 15 (in G.U. 02/03/2023, n. 15); Cutro decree, decreto-legge 10 marzo 2023, n.20, “Disposizioni urgenti in materia di flussi di ingresso legale dei lavoratori stranieri e di prevenzione e contrasto all'immigrazione irregolare”; decreto-legge 5 ottobre 2023, n. 133 reca misure urgenti in materia di immigrazione e protezione internazionale, e per il supporto alle politiche di sicurezza e la funzionalità del Ministero dell'interno”.

[19] Conferenza stampa del Consiglio dei Ministri n. 24 a Cutro, 9.3.2023, https://www.youtube.com/live/51uHPKrCYX4; Italia Oggi, “Strage di migranti: Piantedosi, nessuna connessione tra naufragio e decreto ONG”, 7.3.2023, https://www.italiaoggi.it/news/strage-di-migranti-piantedosi-nessuna-connessione-tra-naufragio-e-decreto-ong-202303071317029239 ; for details on subsequent shipwrecks that belie the minister’s defence, see IOM, Missing Migrants Project infosheets, https://missingmigrants.iom.int/region/mediterranean ; https://missingmigrants.iom.int/region/africa; Pressenza, F. Vassallo Paleologo, International investigation into state massacres in the Ionian Sea, 18.6.2023, https://www.pressenza.com/2023/06/international-investigation-into-state-massacres-in-the-ionian-sea/

[20] Solomon, “It was already too late”: Frontex blames the Hellenic Coast Guard for the Pylos shipwreck, 1.2.2024, https://wearesolomon.com/mag/format/feature/it-was-already-too-late-frontex-blames-the-hellenic-coast-guard-for-the-pylos-shipwreck/

[21] FragdenStaat, OLAF Final Report on Frontex, CASE No OC/2021/0451/A1, October 2022, https://fragdenstaat.de/dokumente/23397 -olaf-final-report-on-frontex/ ; https://fragdenstaat.de/en/blog/2022/10/13/frontex-olaf-report-leaked/

[22] Statewatch, 4 May 2020, “Mediterranean: as the fiction of a Libyan search and rescue zone begins to crumble, EU states use the coronavirus pandemic to declare themselves unsafe”, https://www.statewatch.org/analyses/2020/mediterranean-as-the-fiction-of-a-libyan-search-and-rescue-zone-begins-to-crumble-eu-states-use-the-coronavirus-pandemic-to-declare-themselves-unsafe/

[23] Times of Malta, Persons of trust and missing documents: Malta’s secretive migration project, 3.7.2023, https://timesofmalta.com/article/persons-trust-missing-documents-malta-secretive-migration-project.1041371

[24] Malta Today, Migrants' Libya pushback case dismissed on procedural point, 6.3.2024, https://www.maltatoday.com.mt/news/court_and_police/127949/migrants_libya_pushback_case_dismissed_on_technicality ; Times of Malta, Asylum seekers’ human rights claim thrown out over a technicality, 6.3.2024, https://www.timesofmalta.com/article/judge-throws-asylum-seekers-human-rights-claim-technicality.1087909

[25] Euronews, 5.3.2024, “Frontex director general replies to Ombudsman: 'We're not the European rescue agency'”, https://www.euronews.com/my-europe/2024/03/05/frontex-director-replies-to-ombudsman-were-not-the-european-rescue-agency ; EUobserver, 5.3.2024, “Frontex defends not issuing Mayday alert on Pylos shipwreck”, https://euobserver.com/migration/158179

[26] OJEU, L196/125, 25.7.2022, Political and Security Committe Decision (CFSP) 2022/1295 of 19 July 2022 on the reconfirmation of the authorisation of the European Union military operation in the Mediterranean (EUNAVFOR MED IRINI) (EUNAVFOR MED IRINI/3/2022), https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX%3A32022D1295

[27] See note 25

[28] Ente Nazionale Aviazione Civile, Ordinanze 2024 Sicilia occidentale, https://www.enac.gov.it/la-normativa/normativa-enac/ordinanze/sicilia-occidentale/ordinanze-2024-sicilia-occidentale

[29] Sea Watch, Italy bans human rights monitoring over the Mediterranean, 8 May 2024, https://sea-watch.org/en/italy-bans-human-rights-monitoring-over-the-mediterranean/

[30] A-DIF, Dall’ENAC ordinanze illeggittime contro il soccorso civile nel Mediterraneo centrale, 8 May 2024, https://www.a-dif.org/2024/05/08/dallenac-ordinanze-illegittime-contro-il-soccorso-civile-nel-mediterraneo-centrale/

[31] Legal Centre Lesvos press release, 21.5.2024, “The nine accused of the Pylos shipwreck acquitted based on the lack of jurisdiction of Greek courts”, https://legalcentrelesvos.org/2024/05/21/the-nine-accused-of-the-pylos-shipwreck-acquitted-based-on-the-lack-of-jurisdiction-of-greek-courts/

Our work is only possible with your support.

Become a Friend of Statewatch from as little as £1/€1 per month.

Further reading

Charting a course through the labyrinth of externalisation

“Migration is a European challenge which requires a European response” has become a favoured refrain of EU officials and communiques. While the slogan is supposed to reinforce the need for a unified EU migration policy, it also masks the reality of the situation. The EU’s response to migration – in particular, irregular migration – is increasingly dependent on non-EU, and non-European states. Billions of euros and huge diplomatic efforts have been expended over the last three decades to rope non-EU states into this migration control agenda, and the process of externalisation is accelerating and expanding. Understanding the institutions and agencies involved is a crucial first step for anyone working for humane EU asylum and migration policies.

Frontex and deportations, 2006-22

Data covering 17 years of Frontex’s deportation operations shows the expanding role of the agency. We have produced a series of visualisations to show the number of people deported in Frontex-coordinated operations, the member states involved, the destination states, and the costs.

The politics behind the EU-Mauritania migration partnership

On 7 March, the EU and Mauritania signed a landmark “migration deal.” This January note from the European Commission makes the case for the deal to EU member state representatives in the Council. Dated 26 January, and therefore preceding both the public announcement of the deal on 7 February and its signing one month later, the note offers insight into the politics behind the migration partnership deal between Mauritania and the EU.

Spotted an error? If you've spotted a problem with this page, just click once to let us know.