UK: Over 1,300 people profiled daily by Ministry of Justice AI system to ‘predict’ re-offending risk

Topic

Country/Region

09 April 2025

Over 20 years ago, a system to assess prisoners’ risk of reoffending was rolled out in the criminal legal system across England and Wales. It now uses artificial intelligence techniques to profile thousands of offenders and alleged offenders every week. Despite serious concerns over racism and data inaccuracies, the system continues to influence decision-making on imprisonment and parole – and a new system is in the works.

Support our work: become a Friend of Statewatch from as little as £1/€1 per month.

Image: Michael Grimes, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Summary

- The Ministry of Justice uses artificial intelligence techniques to ‘predict’ the risk of re-offending of thousands of prisoners and people on probation every week

- Figures from January obtained by Statewatch show that 9,420 assessments were completed in one week – more than 1,300 assessments every day

- There are longstanding concerns over bias and inaccuracies in the underlying data, with one former prisoner telling Statewatch that the system is “a classic case of ‘garbage in, garbage out’”

- Prisoners have also raised concerns that they have been unable to challenge inaccuracies and falsehoods stored in the system

- The government is planning to replace the current system with a new “digital tool” in 2026

Re-offending ‘prediction’ software

A Ministry of Justice system which uses AI for ‘predicting’ the risk of reoffending is used on more than 1,300 people in prison and probation services across England and Wales every day, figures obtained by Statewatch reveal.

The Offender Assessment System (OASys) has been in use since 2001. More than seven million “scores” (pdf) setting out people’s alleged risk of re-offending were held in the system’s database as of January this year.

In just one week, from 6 January to 12 January, a total of 9,420 assessments were completed (pdf). This equates to more than 1,300 assessments every day.

The Offender Assessment System (OASys)

OASys was developed by the Home Office through three pilot studies. It was then rolled out across the entire prison and probation system in England and Wales between 2001 and 2005 to manage and assess over 250,000 people every year. The system has been in place ever since.

According to His Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service (HMPPS), OASys “identifies and classifies offending related needs,” and assesses “the risk of harm offenders pose to themselves and others.” It uses machine learning, a form of artificial intelligence (AI) through which a computer system ‘learns’ from data inputs to adapt the way it functions.

“From these assessments, sentence plans are drawn up within OASys to manage and reduce these risks,” HMPPS says, making it possible to “help target interventions, making them more effective, and contribute towards reducing reoffending and protecting the public.”

The risk scores are used to inform a wide range of decisions with enormous effects for people’s lives, including:

- bail;

- sentencing;

- the type of prison to which someone will be sent;

- access to education and rehabilitation programmes; and

A 2013 article in Inside Time, the national newspaper for prisoners and detainees, said the assessment is “the most influential document in the sentence planning and management process and that it is therefore extremely important that it is unbiased and factually correct.”

Help us expose more 'predictive' policing and prison technologies

Become a Friend of Statewatch

Generating “risk scores”

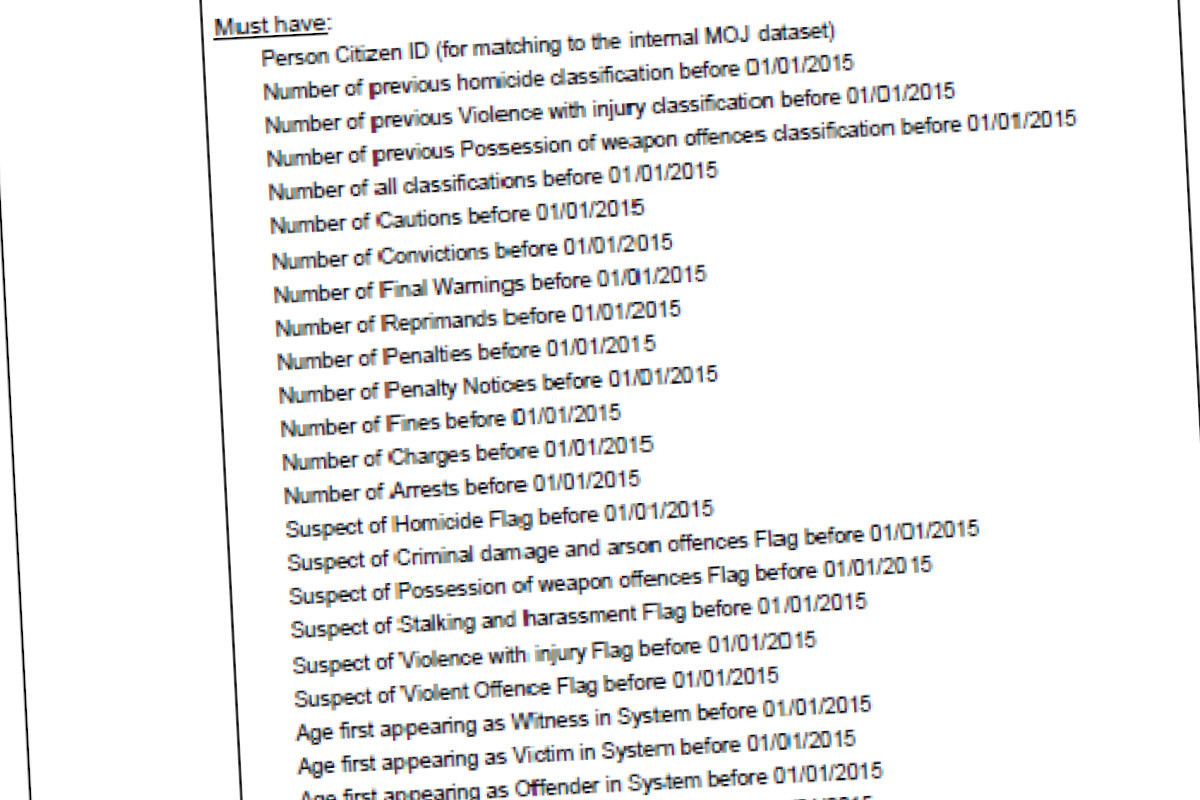

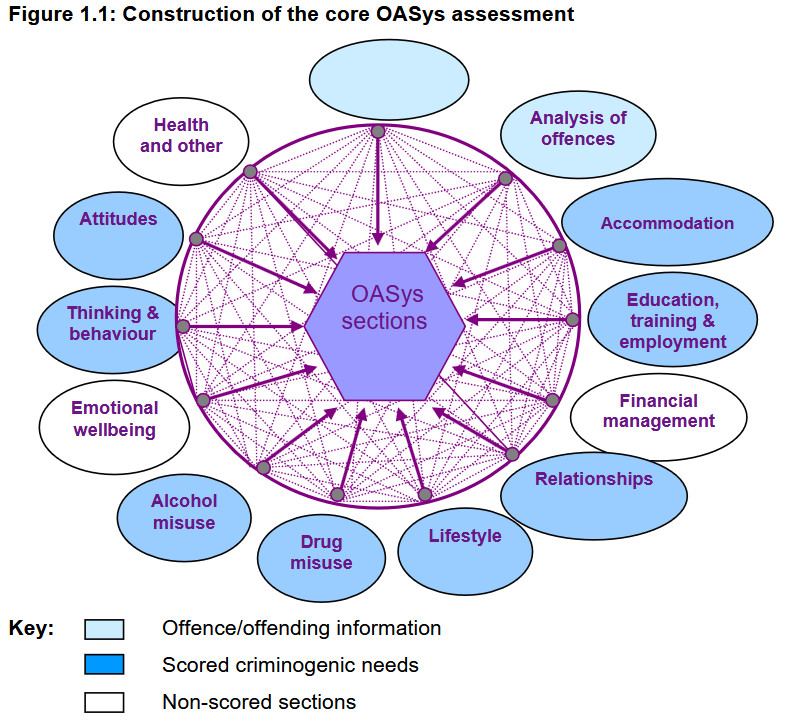

The Ministry of Justice (MoJ) says OASys uses a combination of “structured professional judgement” and risk prediction algorithms to generate “risk scores.” The manual assessment, usually conducted by the Prison Offender Manager (POM, a Prison Service official), gathers information on the following categories (pdf):

- offence analysis;

- accommodation;

- education, training and employment;

- financial management and income;

- relationships;

- lifestyle and associates;

- drugs;

- alcohol;

- emotional wellbeing;

- thinking and behaviour;

- attitudes; and

- health.

Construction of the core OASys assessment. Source: National Offender Management Service (pdf)

OASys algorithms

An MoJ spreadsheet (.xlsx) contains a selection of the OASys algorithms.

One is the OGRS 3 calculator (Offender Group Reconviction Scale). Users have to input “offender characteristics” including gender, “number of previous sanctions,” age at “current conviction” and “first sanction.” The offence type is chosen from a drop-down menu.

Depending on the inputs, the calculator produces risk scores, expressed as a percentage, indicating the “likelihood of any proven reoffending” within one and two years.

Other algorithms are built on top of the ‘predictions’ produced by the OGRS 3.

The OGP (OASys General reoffending Predictor) and OVP calculators (OASys Violence Predictor) use OGRS 3 risk scores, as well as scores from sections of the manual assessment questionnaire undertaken by the Prison Offender Manager.

The latter include sections such as:

- “accommodation”;

- “employability”;

- “drug misuse”;

- “thinking and behaviour”;

- “temper control”;

- “attitudes”; and

- “current psychiatric treatment, or treatment pending”.

Dr Philip Howard, the Head of Risk Assessment Data Science at the Ministry of Justice, has explained on a podcast how the OASys algorithms were built:

“We use information from the probation and prison caseload systems and we combine that with the Police National Computer… we’re combining these different datasets to give us a group of people and then we follow them up again using the Police National Computer so we have the risk factors and the reoffending all combined in these large datasets.”

“Garbage in, garbage out”: concerns over biased data

Melissa Hamilton and Pamela Ugwudike, legal scholars at the universities of Surrey and Southampton respectively, have said the use of crime data in OASys “raises serious ethical questions.” This is because “racially biased policing can permeate the data, ultimately biasing predictions”.

Similarly, in a report on new technologies in the justice system, the House of Lords Justice and Home Affairs Committee said they heard “repeated concerns about the dangers of human bias contained in the original data being reflected, and further embedded, in decisions made by algorithms.”

The report also says issues of bias were raised over 200 times in written evidence alone from lawyers, academics, civil society, technology and human rights experts, and criminal legal authorities.

As well as emphasising threats to equality rights, the Committee warned of “serious risks that an individual’s right to a fair trial could be undermined by algorithmically manipulated evidence.”

Sobanan Narenthiran is a former prisoner and now Co-CEO of Breakthrough Social Enterprise, an organisation “that supports people at-risk or with experience of criminal justice system to enter the world of technology.”

He told Statewatch via email that “structural racism and other forms of systemic bias may be coded into OASys risk scores—both directly and indirectly.” Information entered in OASys is likely to be “heavily influenced by systemic issues like biased policing and over-surveillance of certain communities,” he argued.

“For instance, Black and other racialised individuals may be more frequently stopped, searched, arrested, and charged due to structural inequalities in law enforcement,” Narenthiran said. “As a result, they may appear ‘higher risk’ in the system, not because of any greater actual risk, but because the data reflects these inequalities. This is a classic case of ‘garbage in, garbage out.’”

Official assessment of accuracy and bias

An official evaluation of the risk scores produced by OASys found discrepancies in accuracy based on gender, age and ethnicity. The study found that:

“Relative predictive validity was greater for female than male offenders, for White offenders than offenders of Asian, Black and Mixed ethnicity, and for older than younger offenders. After controlling for differences in risk profiles, lower validity for all Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BME) groups (non-violent reoffending) and Black and Mixed ethnicity offenders (violent reoffending) was the greatest concern.”

This means that OASys scores were disproportionately less accurate for racialised people than white people, and especially so for Black and mixed-race people.

The same study concluded that: “Among all offenders, actual (proven) reoffending was significantly below the predicted rate”.

Higher risk scores – which the system tends to produce, according to the official evaluation – may lead to harsher decisions on sentencing, bail, categorisation, and release.

Inaccurate or false information added to the system during the manual assessment will also affect accuracy ratings. This may be the result of bias and discrimination, carelessness, or insufficient training and resources.

As an official prison service guide on the system from 2005 put it: “A completed OASys is only as good as the quality of the information on which it is based.”

“The ultimate act of dehumanisation”: being profiled by OASys

Statewatch has spoken with several people in prison who reported discriminatory and false information and inaccuracies in their OASys assessments, and the seeming impossibility of challenging these assessments.

Several Black and minoritised ethnic people said their assessors entered a discriminatory and false “gangs” label in their OASys reports, with no evidence and racist assumptions. One man said that a “gangs” label was later added into his report, based on his associates while in prison.

Other people explained that basic, but crucial, details about their cases were entered incorrectly into their OASys reports.

This included the wrong offence type or wrong number of offences being listed, including much more serious offences being put on their report, or information about their co-defendant being falsely cited as theirs. This then impacted their OASys scores.

One person explained that he tried challenging his risk score after it was raised part way through his sentence, only to face negative consequences as a result. He was accused of “offence paralleling behaviour”. He pointed out that prisoners are meant to have the same data protection rights as everyone else.

A man serving a life sentence who spoke to a researcher at the University of Birmingham explained the impact of inaccurate data entries in his OASys assessment:

“I have likened it to a small snowball running downhill. Each turn it picks up more and more snow (inaccurate entries) until eventually you are left with this massive snowball which bears no semblance to the original small ball of snow. In other words, I no longer exist. I have become a construct of their imagination. It is the ultimate act of dehumanisation.”

Sobanan Narenthiran told Statewatch that “my fellow prisoners would warn me about the OAsys assessment - they explained how vulnerable honesty can lead to penalisation. If you talk too freely about the 'risk factors' in your life, your progression, privileges and chances of parole can be reduced significantly”.

He also described how difficult it was to challenge incorrect data in his OASys report, which led to an unjust decision:

“To do this I needed to modify information recorded in an OASys assessment, and it’s a frustrating and often opaque process. In many cases, individuals are either unaware of what’s been written about them or are not given meaningful opportunities to review and respond to the assessment before it’s finalised. Even when concerns are raised, they’re frequently dismissed or ignored unless there is strong legal advocacy involved.”

Support more work like this

Become a Friend of Statewatch

New digital tools on the way

Despite serious concerns for equality and discrimination, fair trial rights, accuracy, and opportunities for redress, the Ministry of Justice continues to use OASys assessments across the prison and probation services.

The Ministry of Justice told Statewatch in response to a freedom of information request (pdf) that “the HMPPS Assess Risks, Needs and Strengths (ARNS) project is developing a new digital tool to replace the OASys tool.”

An early prototype of the new system has been in the pilot phase since December 2024, “with a view to a national rollout in 2026.” ARNS is “being built in-house by a team from [Ministry of] Justice digital who are liaising with Capita, who currently provide technical support for OASys.”

The government has also launched an “Independent Sentencing Review”. This is looking at how to “harness new technology to manage offenders outside prison”, including the use of ‘predictive’ and profiling risk assessment tools, as well as electronic tagging.

Capita, one of the UK’s biggest outsourcing companies for the public sector, has held the contract for managing electronic tagging services in the UK since 2014. The company is also supplying a growing number of UK police forces with COSAIN, a social media surveillance tool, for monitoring activists.

Documentation

- Freedom of Information Request response from the Ministry of Justice, Ref No. 250107008, dated 28 February 2025 (pdf)

- OASys Blank Template, obtained via Freedom of Information Request response from the Ministry of Justice, Ref No. 250107008, dated 28 February 2025 (pdf)

- Ministry of Justice OGRS3 OGP and OVP calculator (.xlsx)

Our work is only possible with your support.

Become a Friend of Statewatch from as little as £1/€1 per month.

Further reading

Press release: Turkey: Algorithmic persecution based on massive privacy violations used to justify human rights abuses, says new report

More than 13,000 Turkish military personnel have been dismissed since July 2016 on the basis of an algorithm used by the authorities to assess the alleged “terrorist” credentials or connections of military officers and their relatives in violation of multiple human rights, says a new report published today by Statewatch. [1]

Europe: Prison population continues to decline, overcrowding remains a serious problem

Imprisonment rates continue to fall, find the latest Council of Europe penal statistics, although the report says this is due to the inability to prosecute cyber-enabled criminal offences rather than a shift away from incarceration as a form of punishment. Drug offences remain the reason for most convictions leading to imprisonment, making up 17.7% of the total prison population. The CoE press release also highlights that overcrowding remains a serious problem in a number of member states.

Spotted an error? If you've spotted a problem with this page, just click once to let us know.